Every Path Leads Us Home | My Three-Year Story with CCE

Issue date:2026-01-29

At the beginning of this story, I am expected to introduce myself.

I lingered over it longer than I care to admit. How does one describe oneself? How does one decide which words are worthy of standing at the door of a life?

"Hi, my name is Judy Hu. I graduated from UWC Changshu China in 2024. Now, I am a sophomore at the University of California, Berkeley."

That is unbearably plain.

So, I hesitated. I thought about how I wished to be known, not merely by others, but by myself. I realized that an introduction is more like a declaration of becoming. That realization reminded me of a sentence I had been afraid to pronounce for a long time.

To say it aloud felt like placing a burden upon myself, as though the words, once spoken, would demand a life to match them.

But if I am to speak honestly of what these three years at UWC Changshu have done to me—how they reshaped my sense of responsibility, belonging and voice—then silence would be a greater dishonesty.

So, please allow me to begin again.

My name is Wenrui Hu, and I am a director.

"A light rain renews all things;

a single thunder awakens spring."

Before I came to UWC Changshu, my world was bounded.

I was born in Jinhua, Zhejiang, a modest city more often known for its cured ham than anything else.

As a child, I lived in Yangjia Village, tucked deep into the northern mountains of Jinhua.

It was a village of barely a dozen households, sparse in buildings but abundant in life: chickens, ducks, and geese roaming freely; old brick walls warming themselves in the afternoon sun; narrow paths where mountain winds passed through, unhurried, in every season.

The adults spoke endlessly about prices, neighbors, and the small frictions of daily life. At the village entrance, fragments of gossip drifted in and out, carried by passing voices.

These ordinary sounds became my earliest understanding of the world.

Growing up in such a place, one's beginning is often small.

Yet it is precisely because the beginning is small that one learns to look outward.

Mountains may block the eye, but they do not restrain curiosity.

Chinese writer Yu Qiuyu once wrote that beyond walking, the heart, too, is in search of a greater world. And when that longing awakens, a person's fate begins its quiet migration.

After primary school, my life took on a nomadic rhythm. I moved between Hangzhou and Shanghai, sat for countless exams, applied to school after school, and finally, almost as if guided by fate, arrived at UWC Changshu.

People often say that opportunity favors the prepared. My first encounter with CCE, however, came by accident.

When I first entered CSC, I was overwhelmed by the abundance of possibilities: Zhi Xings, social service, theater, design, sports... The world suddenly expanded faster than I could orient myself within it.

Interview followed interview. I must have seemed painfully unsure, stumbling over my words, uncertain of what to say, missing several projects I had genuinely hoped to join.

I felt disheartened—not because I needed to belong to any particular group, but because I began to doubt whether I possessed anything distinctive at all.

▲My House-Heimat

As time ran out and most Zhi Xings closed their recruitment, I received an email announcing that the Chinese Cultural Evening (CCE) was seeking directors. I thought this might be my last chance.

I also thought, perhaps with a mixture of hope and self-deception, that I had some affinity for language. Without much hesitation, I applied for the position of Language Director, a small branch within the directing team.

The interview differed from the others. It felt formal, almost ceremonial. When I entered the room, a row of senior directors faced me, and my composure dissolved immediately.

I listed my experiences—few in number, unremarkable in brilliance. Silence settled in, thick and awkward.

Then, April, the executive producer at the time, asked:

"If your team members fail to complete the script by the deadline, what would you do?"

I paused for a moment and replied, "I would first ask what difficulties they were facing. And if the script truly couldn't be finished, I would help them write it."

Looking back, I realize that this was likely the first moment in which I revealed a director's instinct. It hardly has any relevance to technique, but to attitude: when a gap appears within the group, are you willing to step forward?

That seemingly ordinary answer became the beginning of my journey with CCE, but admittedly, that is how it started.

"By the dim lamp, a flavor emerges;

in first light, clarity is born."

In my first year with CCE, I thought of it simply as an evening performance when everyone gathered to celebrate Chinese New Year.

It became my first real encounter with directing. I moved cautiously, almost timidly. Before making any decision, I sought reassurance from Yoyo, the chief director at the time. Every idea asked for permission before daring to stand on its own.

As Language Director, my responsibilities were, on paper, quite clear: to assist with writing hosting scripts with the hosts, to oversee language-based programs, and to participate in program reviews.

I assumed I would be providing support, performing a function. I did not yet know that I was about to become a creator.

When the theme "Prayers and Blessings" was announced, a restlessness stirred. Simple host transitions between programs felt insufficient, as though something essential had been left unsaid.

Almost on impulse, I offered a small idea: what if we framed the evening as a story? What if a wishing tree stood at its center, and through it, the programs spoke to one another?

It was a suggestion made lightly, without expectation. I assumed it would dissolve among stronger, more confident proposals. Instead, it was met with an openness I had not anticipated. No one dismissed it; instead, everyone stepped in.

For weeks, the stage designand directing teams took turns occupying the common room, twisting steel wire into the shape of a tree, patiently suspending red slips of paper from its branches—each bearing a program's name, each carrying a handwritten wish. What had begun as an abstract idea slowly took on weight, texture, and presence.

In classrooms, the hosts and I let our imaginations wander freely. Stories surfaced from everywhere: Marco Polo setting out across unknown lands; a band's lead singer waiting for the moment to be heard; a traveler who misses a flight; a penguin displaced by warming seas; two strangers meeting for the first time in a Jiangnan water town; a boy repairing his violin with a shopkeeper; an aging Tang Dynasty painter who can no longer paint.

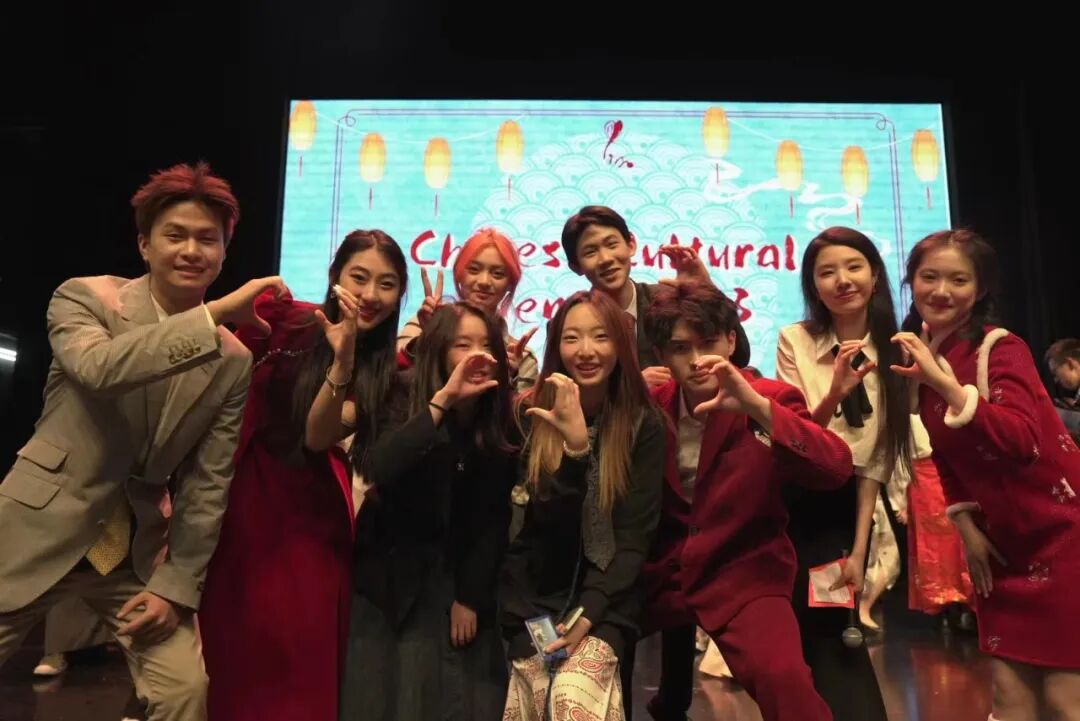

▲A group photo with the hosts

Through poetry, theater, and small scenes, we shaped our understanding of tradition as something living, capable of being entered from countless directions.

Throughout it all, the feeling of working together toward a single dream returned to me again and again, gradually insisting on a truth I was only beginning to grasp: no man is an island.

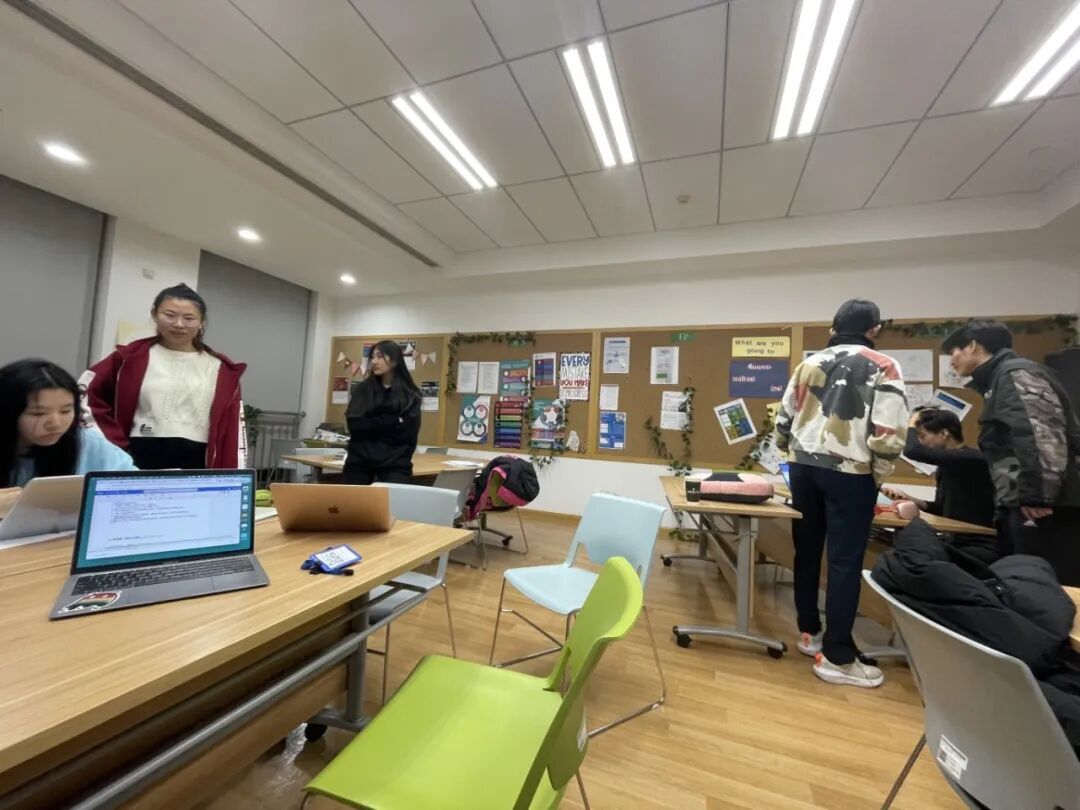

▲ A group photo featuring the working committee

When the performance began, the spotlight settled upon the wishing tree. Program titles, handwritten wishes, and red paper trembled softly beneath the light, and something stirred quietly within me.

Standing off stage, I felt what Durkheim meant when he wrote that great acts cannot be accomplished by individuals alone, that only through the collective does action acquire its shape.

"The storm thickens,

the sky darkens—

yet the rooster continues to crow."

▲2023 CCE

In my second year with CCE, entrusted by the confidence of others, I became the Chief Director of CCE 2023.

Chaos defined that year. On December 12, 2022, pandemic restrictions lifted suddenly, and the school announced the possibility of early closure. Time, once abundant, collapsed inward.

Li Ping, the executive producer, told me we had one week to complete the performance or postpone it until February. The choice felt brutal. Almost nothing stood ready. Yet postponement threatened to dissolve months of labor into uncertainty.

When I shared the news in the group chat, messages flooded in—overlapping, urgent, unreadable. I sat alone in a library corner, watching the screen refresh again and again. I typed, erased, rewrote, erased again. Finally, I sent one sentence:If you're free, come to the learning center so we can discuss this together.

Far more people arrived than I had expected. Within minutes, the sofas were surrounded by program leaders, the directing team, and supervisors. I explained the situation with a voice that betrayed my anxiety, yet the response I feared never came.

Instead, my friend Edward said to me: "Whatever decision you make, we will support you unconditionally."

Ten minutes later, we made the bravest decision we could.

We would complete the entire performance in one week.

From that moment on, CCE stopped being an idea and became a reality. We reassigned roles. Tightened schedules. Measured time. Secured materials. Rewrote processes.

Esther, head of Chinese Performing Arts, told me to trust her team completely so I could focus elsewhere.

China Band, the dragon and lion dance teams, the orchestra—each group took responsibility for its own rehearsals with determination and an organized manner that felt almost unreal.

Kiki, our stage design director, and the tech crew spent nearly every waking hour with me in the theater, purchasing props, constructing sets, and designing lighting and sound.

One night, as the six hosts and the directing team gathered in a classroom to write, someone said casually, "If this year's theme is guardianship and remembrance, why not let the story unfold in a photo studio?"

▲Writing scripts with the hosts

From that single suggestion, everything began to converge.

Kyrie and Isabella saw in the landscapes of Chinese dance a space for an aging painter who had lost his inspiration, and for a passing traveler who pauses only briefly.

Jonathan and Barley thought of Glorious Years and the era it carried with it, placing the stories of a previous generation upon the walls of the studio.

Zhengru, having read The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, spoke of its quiet romance and how well it suited the program's atmosphere. Amelie brought Gao Qi's Nine Poems on Plum Blossoms, imagining the photo studio as a place that, like the plum blossom, leaves its trace long after winter has passed.

That night, we wove all of it together. By morning, more than four thousand words had been written.

Months later, when we watched Farewell, Photo Studio appear on the CCTV Spring Festival Gala, we were struck by an almost absurd sense of recognition, as though our own sparks had been answered, unexpectedly, by the wider world.

However, the performance was eventually postponed.

▲After the CCE was postponed, our working

committee got together for an online meeting

By February 14, 2023, when we were finally cleared to take the stage, the performance itself had already loosened its hold on me.

As we ran together for the curtain call, I felt that what mattered was not the evening we had survived, but the fragile, enduring knowledge that something had been formed between us and would not simply disappear when the lights went out.

I hoped that this might remain as a memory worth carrying, and that CCE might grow beyond the role of a cultural "representative" into a living act of belief, sustained by warmth, courage, and shared responsibility.

CCE 2023 was a year of uncertainty and trial, and it is the one I remember most vividly.

Perhaps it was only when we reached the place where the river seemed to end that we discovered it did not end at all. And sitting still, watching the clouds rise, we realized that the story was beginning anew.

"At the river's end, we sit still and watch the clouds rise."

In my DP2 year, I stepped into a different role. I became a senior consultant to CCE, a more instructive role.

The pandemic had begun to recede, and international students finally returned to the CSC campus. It was then that we realized something unmistakable: that the cultural language we had long taken for granted was no longer self-evident to everyone who stood before it.

What once required no explanation now demanded care.

We had to explain again.

To translate again.

To search again and to learn.

The hosting scripts grew clearer. The programs became lighter in spirit, more generous in humor. Cultural storytelling shifted toward something more open, more patient, more international.

That year, CCE moved beyond the shape of a Spring Festival gala. It became a place of encounter, a medium where cultures did not simply present themselves, but listened to one another, adjusted, and met halfway.

And perhaps this, too, was a kind of arrival.

How does one invite others through a single door, into a culture not their own? And what, in the end, do we hope to leave with the world?

▲Screenshot of the interview video

▲Screenshot of the interview video

with the directors' team.

Somewhere along the way, I found myself becoming a person who could decide, who no longer hesitated endlessly, who could choose and bear the consequence of choosing.

Standing onstage during the final curtain call, I felt momentarily disoriented, caught between gratitude for CCE and an awareness of how quietly, irrevocably, I had changed.

Only then did I realize that three years had passed, and that I, too, had become what people half-jokingly call a DP2.

I have spoken at length, yet even now it feels impossible to fully articulate what CCE has come to mean to me. Words can describe events, but they falter before memory.

I often think about the night CCE 2023 ended. Long after the applause faded, I was alone in the nearby drama classroom, packing away props.

With the grandeur behind me, my thoughts finally slowed, and I allowed myself to step back and ask what I had avoided asking before: What does CCE really mean to us?

For a long time, I questioned our persistence. After so many difficulties, what continued to sustain us? What, at its core, is a traditional Chinese cultural performance striving for? I doubted. I hesitated.

I wondered whether it deserved such an investment of time and effort, whether it could withstand the weight of so many expectations and disappointments.

▲2024 CCE Working Committee

And then, gradually, I understood what CCE leaves me with. It is the quiet reassurance of countless "received" messages after long lists of task assignments. It is the exhilaration of crafting a line of dialogue that finally feels right.

It is the laughter spilling out of the common room late at night. It is the calm of knowing that every program has arrived on time for rehearsal.

It is watching performances grow, visibly, day by day. It is waving phone flashlights together during Glorious Years. It is the seriousness with which each director reports progress during meetings.

It is Ms. Li Ping and the chairs who never once missed a rehearsal or review. It is a succession of moments, too many to name, that continue to glow.

▲2024 CCE,I participated in

the Chinese dance performance

Back then, I often said that we were less a team than a band of comrades, warriors whose task was to create joy for others. And perhaps joy truly is one of the greatest arts the world can offer.

I remain deeply grateful to have worked alongside people so passionate, focused, and endlessly creative.

The Chinese poet Hai Zi once wrote that a life is measured not by its length, but by the moments that suddenly blaze into light.

To those who gave themselves to CCE, my gratitude is this: through you, I learned how to recognize countless such luminous moments and to know when they were shaping my own.

"Along this arduous journey,

we reach the sky."

In 2025, after graduation, I returned to UWC Changshu to watch CCE rehearsals.

Time had passed, yet the space felt familiar. When the cast moved toward the stage for the final curtain call, something in me loosened. What I saw was a continuation.

Ms. Li Ping asked me quietly whether CCE truly mattered that much to me.

I answered yes, as I had years before during my interview, with certainty.

CCE has never belonged to a single evening. It has always been something one enters. A threshold rather than a stage. Through it, the world feels slightly less rigid, distances slightly less fixed.

In Exit West, Mohsin Hamid imagines doors that open between distant places. Whenever I return to that image, I think of the door we have been building, a door through which one may begin to walk toward China.

Like the Arctic Ocean and the Nile, drawn toward one another within the same humid cloud, what once appeared distant does not remain so forever.

Cultures, people, and hopes follow their own slow currents, converging not by force, but by time. That means, even if we wander, every path will take us home.

Along this arduous journey, we reach the sky.

Through adversity, we press on—until the stars.

CCE and I have never truly parted. What it has given me continues to shape how I listen, how I decide, and how I step forward when something larger than myself begins to call.

Perhaps this is how a journey begins again.

And so, I leave CCE to its own unfolding, trusting that it will continue to find its way.

-End-