From UWC to the World: Shelley Chen's Semester of Learning Across Oceans

Issue date:2026-01-23

When a cruise ship becomes a campus, learning transcends the classroom. Over 100 days at sea, a single voyage spanned 11 countries and regions, transforming travel into the curriculum.

In September 2025, Shelley Chen, a 2024 graduate of UWC Changshu China from Shenyang, participated in Semester at Sea (SAS) as a Davis UWC Scholar, with additional financial support from SAS. Now a sophomore majoring in anthropology at Whitman College, she spent a semester aboard a ship that traveled across continents.

From the Netherlands to South Africa, from Morocco to Thailand, Shelley attended classes at sea and conducted fieldwork on land. Shaped by UWC's cross-cultural approach, the journey became more than an academic program—it was a way to connect academic learning with real-life experiences and understand the world through direct engagement.

▲Shelley (right) and her friend on the ship

1. Interviewer: From Shenyang to UWC Changshu, from Whitman College to Semester at Sea—how did you make each of these choices?

Shelley: I grew up in Shenyang, a typical industrial city in northern China. I completed my early education in the local public school system, which was rigorous and clearly structured.

Choosing to transfer to UWC Changshu for high school was a deliberate decision to diverge from a predictable path. I wanted to step out of my comfort zone and immerse myself in a place where I could genuinely experience global diversity.

I was curious about what happens when young people from over a hundred countries live and learn together. But once I entered such a diverse community, I began to question my own identity: Where do I truly belong? What place can I really call "home"?

As an international student, I was constantly moving. Over time, that movement pushed me to think more deeply about belonging and how we come to understand ourselves.

For a long time, I thought of home as simply a place where you could rest and feel at ease. But after three years at UWC Changshu, I realized there’s another kind of home—one that holds a quieter, intangible strength. It gives you the confidence to see the world on your own terms and the courage to become yourself.

▲Shelley's House at UWC-Meraki

UWC helped me see myself more clearly through everyday life in a shared community: late-night dorm debates about religion and secularism, casual canteen conversations where we shared stories and traditions from home, and even heated card games, where everyone played by different regional rules.

Those small, everyday moments helped me understand who I was within a group. They gave me a steady inner foundation and a clearer sense of my roots.

That foundation shaped my choice to attend Whitman College, known for its liberal arts program, and to anthropology. I wanted to understand how people create belonging, meaning, and connections across cultures. Theory provided me with a framework for understanding the world, but I longed for a space where knowledge and practice could come together.

Then Semester at Sea appeared: one ship, one semester, 11 countries. Just as I was searching for the essence of "home," this journey began.

Semester at Sea has been running for more than sixty years. Over 600 students and faculty live and learn together on a ship that’s both a campus and a bridge into local communities. We crossed oceans and stepped directly into the societies we were studying.

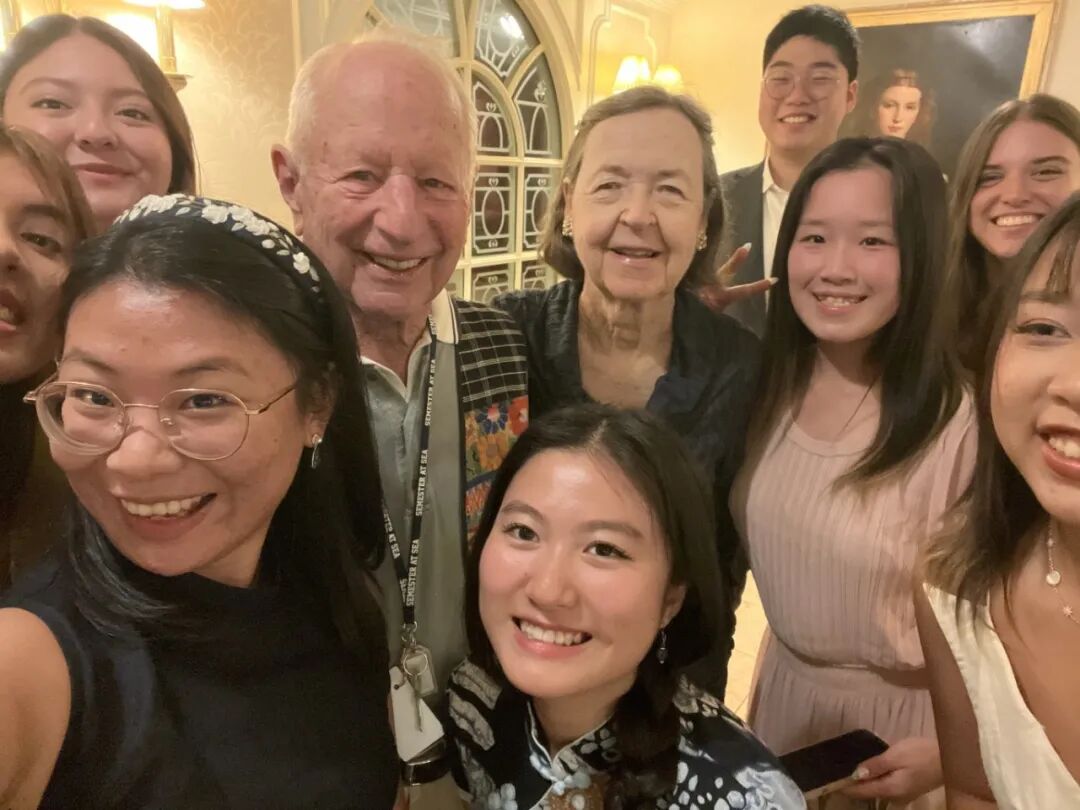

▲During the ship's stop in Vietnam,

the Davis couple came aboard to share a

reunion dinner with UWC Davis Scholars.

As a UWC graduate, I was awarded the Davis UWC Scholarship, with additional financial support from Semester at Sea, which together made my participation possible.

About thirteen UWC alumni from different campuses were on the same voyage, and reconnecting after we’d dispersed across the world felt unexpectedly meaningful.

▲ On September 21, 2025

UWCers celebrated UWC Day together

2. Interviewer: Which countries did you visit, and how did learning work on the ship?

Shelley: This voyage took us to the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Morocco, Ghana, South Africa, India, Vietnam, Hong Kong (China) and Thailand.

Academically, the program is built around two main components: Onboard Classes and Field Classes, which are day-long academic excursions in each port. Global Studies, a required course for all students, connects our voyage route to the politics, economies, societies, cultures and environmental issues of the regions we visit. The other three courses were chosen based on individual interests.

▲U.S.–China Relations Class

All the professors lived on the ship and stayed with us on board for the entire semester. That meant they weren’t only our instructors in the classroom, but also led our Field Classes on site.

Field Classes were much like the field trips I had at UWC. We spent full days with a professor and classmates in one city, diving deeply into local contexts through visits to universities, NGOs, or think tanks. We would attend lectures, participate in discussions, and complete learning goals designed by the professor.

For my International Relations course, our Field Class took place at a university in Casablanca, Morocco. Over shared meals and conversations, we connected with local students and discovered that many of us shared a strong desire to make a difference in the world.

We then entered the classroom, where professors from the host institution introduced key concepts such as soft power, hard power and cultural space. Throughout the session, SAS students and local students actively discussed current global issues together.

▲Field Class at a university in Casablanca

We discussed real-world issues, such as whether Morocco’s plan to build the world’s largest stadium for the 2030 World Cup was sustainable and how it might be used afterward. Local advisors and sustainability NGOs joined the discussion, offering additional perspectives on the challenges the country faces today.

Semester at Sea is a study abroad program with one key difference: the campus itself is constantly moving. It has a full academic system with exams and GPA evaluations, and students can transfer credits back to their home universities.

▲Field Class in Hong Kong China

3. Interviewer: Among all these experiences, what was most valuable to you?

Shelley: I was incredibly lucky. For most of my life, I experienced the world through others' eyes—through books, films and stories. But this time, I was seeing the world with my own eyes and feeling it with my own heart.

Encountering lives so different from mine and exchanging stories created a deep sense of connection. I was no longer just an observer; I became part of the world around me.

Standing on the mountains at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, watching the rocks rise sharply into the sky and the waves crash with overwhelming force, I suddenly felt how small human beings are.

Walking barefoot through the golden sands of the Moroccan Sahara, tracing the footsteps of camels, I let the grains slip through my fingers—and somehow, I felt the longing that drove the Chinese writer San Mao to cross oceans into the unknown. On the morning I left the desert, I remembered The Little Prince and his 43 sunsets, and I imagined the sunrise I saw as his 44th.

As I listened to African drums and swayed to the rhythm, I remembered lessons from my freshman history class. These rhythms once carried resistance and memory during colonial times. They connected communities and preserved a sense of belonging.

▲ At the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa

Every moment felt vivid and real. I cannot point to a single event or scene as the heart of the experience. What stayed with me was a profound sense of life’s vastness.

As Seneca wrote, "Why weep over parts of life? The whole of it calls for tears." This journey deepened my gratitude for life, the world and the people I met. I hope the humility and empathy it sparked in me can ripple outward.

4. Interviewer: Did you face any unexpected challenges during the journey?

Shelley: At the first security checkpoint, I handed my passport to the officer and walked through the metal detector as usual. But when I turned back, my passport didn’t come back to me. Instead, it had been passed directly to the security supervisor. I immediately sensed something was wrong, though I couldn’t imagine why they were holding it.

"I cannot give your passport back," the officer said.

The problem turned out to be my passport holder. It was a small one printed with a hand-drawn world map. The officer told me, very seriously, that the way Morocco’s territorial boundaries were marked on it was inaccurate, and carrying it could cause trouble.

I was shocked at first, but I thanked them for warning me before it escalated into something worse. Their tone softened immediately, and I took the opportunity to propose a solution. I had a train to catch that evening and a hotel check-in ahead of me, so I really needed my passport. I asked whether they could keep the passport holder and return the passport itself.

After confirming that I was giving it up voluntarily, they handed my passport back. My little map remained behind at Casablanca security. Before I left, the officer smiled and gave me a friendly reminder: "Don’t buy too much in tourist areas." He laughed, explaining that tourists are often charged several times more than locals.

Later, I learned why Morocco is so sensitive about territory. Western Sahara’s status remains unresolved, and if you look closely, Google Maps marks the border as a dotted line.

5. Interviewer: As an anthropology student, what did you pay most attention to? How did this connect with your UWC education?

Shelley: I focused on how culture manifests in everyday life—how people shop at markets, use public spaces, switch languages in immigrant communities, organize their families, and express identity through food, clothing and rituals. I wanted to see culture as something dynamic, not static.

In Chinatown in Port Louis, Mauritius, my friends and I visited a small Lanzhou noodle restaurant. A boy of about thirteen took our order, speaking broken English at first. When he heard us speak Chinese, he quietly switched. After finishing his work, he sat in a corner behind the counter.

While paying, I spoke with his mother and learned that they had moved from Lanzhou three years earlier and that he went to a local school. She spoke with practicality and quiet strength, while he stayed silent.

▲Olympics on the cruise ship

In that moment, the anthropological concept of a liminal space came alive. The noodles, the Chinese characters on the sign, and the family-run rhythm of the shop all showed their effort to recreate a sense of home in a foreign land.

His silence revealed another truth: for children of immigrants, adapting to a new culture is not just about language or habits. It is a quiet negotiation of identity. He could easily switch between languages, yet his sense of self as someone from both Lanzhou and Mauritius was still developing.

At UWC, we often talked about migration struggles through literature, film, and theater. In the Global Issues Forum, we analyzed cases and debated policies. But this boy showed me that understanding other cultures requires more than reasoning. It also requires emotional presence. I call this empathy.

▲At UWC Changshu China

6. Interviewer: Did this journey deepen your understanding of UWC’s mission and values?

Shelley: UWC was my first window into the world. In class and in daily conversations with classmates from around the globe, I heard real stories unfolding far away, narrated by peers who had lived them. Semester at Sea brought this perspective to life, allowing me to feel its weight and meaning.

Seeing the boy from Lanzhou in Mauritius or immigrant artisans in a South African market helped me understand what UWC means by connecting cultures. It does not mean erasing differences. It means stepping into unfamiliar situations, understanding someone else’s perspective and feelings, standing with them and taking responsibility for them.

Before flying to the Netherlands, my religion professor said, "Every choice and action should bring you closer to the divine." He didn’t mean "divine" in a strictly religious sense. He meant it as a moral direction: to go beyond the limits of the self, and to move toward a wider human community.

Values like responsibility, empathy and service shaped my decisions in the same way. I spoke up for marginalized groups in class and listened to strangers’ stories while traveling. These small actions shaped my understanding of global citizenship and gave me the courage to connect across differences, stay curious and take responsibility for others.

After living and seeing the world, my idea of home changed. I no longer need to tie it to one place. On the ship, in every honest conversation, I found myself existing with others and for others. I saw people in the crowd, and in their eyes, I saw myself. Everywhere I go can become home. By truly engaging with a place, a moment and its people, I begin to create a sense of belonging.

From Shenyang to Changshu, from Whitman to the world, this journey taught me how to see the world and find my place in it. Anthropology is more than a subject—it is a way to engage with the world and build meaning through action. I carry the perspective that was born at UWC, deepened at sea and that continues to guide me as I seek to understand this complex and beautiful world with humility, depth, and love.

-End-