From Being Questioned to Being Seen: A Chinese Teacher's Journey in Mississippi

Issue date:2026-01-07

"Go back to China!"

The door slammed shut, sending vibrations through the wall. The girl with her backpack had barely disappeared when a shout from the back of the classroom cut through the noise and froze the room.

It was Yixing Lu's first month teaching at Byhalia High School in Mississippi.

In this rural public high school, surrounded by farmland, two-lane roads and the quiet economy of small-town life, Lu was the only Chinese face in the building. She was also the first Chinese national teacher recruited by the Mississippi Teacher Corps in nearly thirty years.

Lu grew up in Zhangjiagang. She later studied at UWC Changshu China, then crossed the Pacific to pursue history at Mount Holyoke College, followed by Advanced Humanities Study at Columbia University. In 2024, she entered a publicly funded Master of Education program at the University of Mississippi. The program required a full-time teaching placement at Byhalia High.

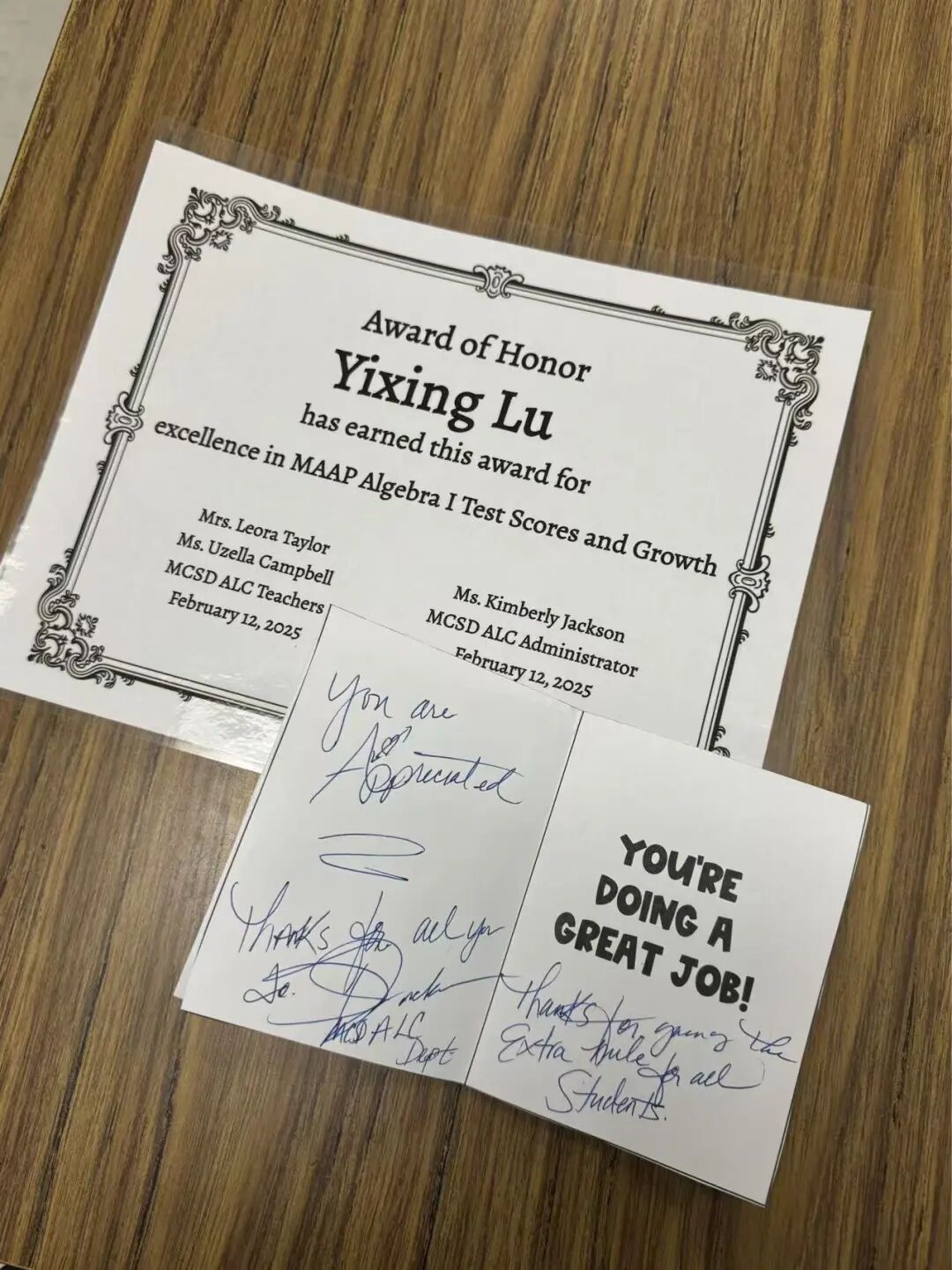

The placement came at a moment of shortage. Byhalia High urgently needed math teachers. Drawing on a rigorous academic foundation shaped by China's national curriculum and a perfect SAT Math score, Lu passed the mathematics licensure exam with full marks and earned U.S. teaching certification in both Secondary Social Studies and Algebra I. The course she was assigned, Algebra I, was not just another class. It was a gatekeeping subject, one that could determine whether students graduated and affect the school's accountability rating.

A year later, the numbers would tell a story few could have predicted. Among nearly 120 students she taught, the pass rate on the state exam rose from 56% on the district benchmark to 95%. Students in the lowest-performing quartile showed growth exceeding 100%. The results contributed to the school's highest rating in nearly six years.

But none of that was visible at the beginning. In those early weeks, there was only a windowless classroom, constant noise and the unmistakable sense that she had stepped into a world that did not want her.

Arriving in Mississippi:

Being Told to "Go Back"

In August 2024, I walked into my classroom carrying what felt like a newly lit flame.

Each morning, I greeted students with a big smile. I filled the space with energy. I planned meticulously. I color-coded practice sets. I built games, competitions and small rewards. I believed that sincerity, applied consistently, would spread.

It didn't.

What came back to me was chaos.

One Wednesday, not long after class began, a student interrupted loudly.

"I need to use the bathroom."

She already had her phone pouch in hand and backpack on her shoulder. Byhalia's policy was clear: no leaving during the first and last fifteen minutes of class and a strict limit on bathroom passes to reduce vaping, truancy and hallway fights. Veteran teachers had coached me on the numbers. Five passes per month was "more than enough." Emergencies could be managed by trading passes.

I refused.

She stormed out and slammed the door.

The wall shook. A student in the back shouted, "Go back to China!"

After the bathroom incident, I filled out the referral. The student was sent to in-school suspension. I told myself this was what consistency looked like. I thought I would finally be able to breathe.

I couldn't.

After the second block, I bent down and picked up fourteen crumpled paper balls from the floor. Students had taken turns throwing them at my back while I knelt beside a classmate, trying to explain a math problem.

By the final class of the day, even my "good" students felt unreachable.

A usually high-performing girl lay with her head on the desk. I asked her once, twice, then a third time, to sit up and listen. She didn't move. Without lifting her face, she said, loud enough for the room to hear:

"I'm not sleeping. You just don't know how to teach. That's why I put my head down."

When the dismissal bell rang, the room emptied.

I stood alone, staring at paper balls scattered across the floor and pencils crushed beneath chair legs. In the sudden quiet, a sharp confusion rose in me:

Did I still recognize myself?

Standing at the center of that classroom all day, I had felt like a target. But in the silence, something else became clear.

The students weren't resisting me as a person. They were resisting the cold, unyielding authority they believed I represented. Without realizing it, I had made myself its spokesperson.

They were frustrated by the ninety-five-minute math block. They had nowhere to place the irritation that had built up, so they placed it on the most visible, most exposed person in the room: the teacher at the front.

Each sneer and retort carried not just defiance, but a weight they didn't know where else to put.

My instinct was to strike back. To harden my expression. To raise my voice. To write office referrals and let punishment absorb the conflict.

I didn't understand yet that the more I leaned on consequence, the more the room slipped away from me, until I could no longer recognize myself inside it.

The Punishment Ladder

and the Distance It Created

My classroom had no windows.

For security reasons, even the door window was covered with a piece of cloth. Only a small circular opening remained for administrators to look through during walkthroughs.

Under harsh fluorescent lights, the room felt less like a classroom and more like a holding space: desks with hardened gum underneath, the low hum of the air conditioner and a group of teenagers whose first instinct was to escape.

Byhalia is a town of about 1,339 people. Community resources are scarce. There is only one grocery store that reliably sells fresh vegetables. Owning a car is not a convenience here; it is a condition of survival.

The drive from school to my shared rental took ten minutes. Walking took an hour, along highways without sidewalks. Uber would tell me the nearest car was "over an hour away."

After school, I often waited alone in my classroom until my roommate finished work and could drive me home. On weekends, even taking the dog for a walk meant hugging the edge of the road, pressed close to the traffic lane.

In my classroom, every student was either a local or a Mesoamerican immigrant. In the entire town, I saw no other Asian face.

On the first day, I introduced myself: my hometown, my university, my background. The students stared in silence. Later, I learned that many of them had never left the county. Their parents worked in nearby factories and industrial parks. For them, public high school was not a bridge to faraway possibilities. It was a step toward a stable job at a factory close to home.

A few days in, they realized I couldn't understand their local dialect. Exclusion followed. So did mockery.

I pretended not to notice. I simplified my language to the bare minimum and relied heavily on visuals. I was afraid my accent would become yet another excuse for them to disengage.

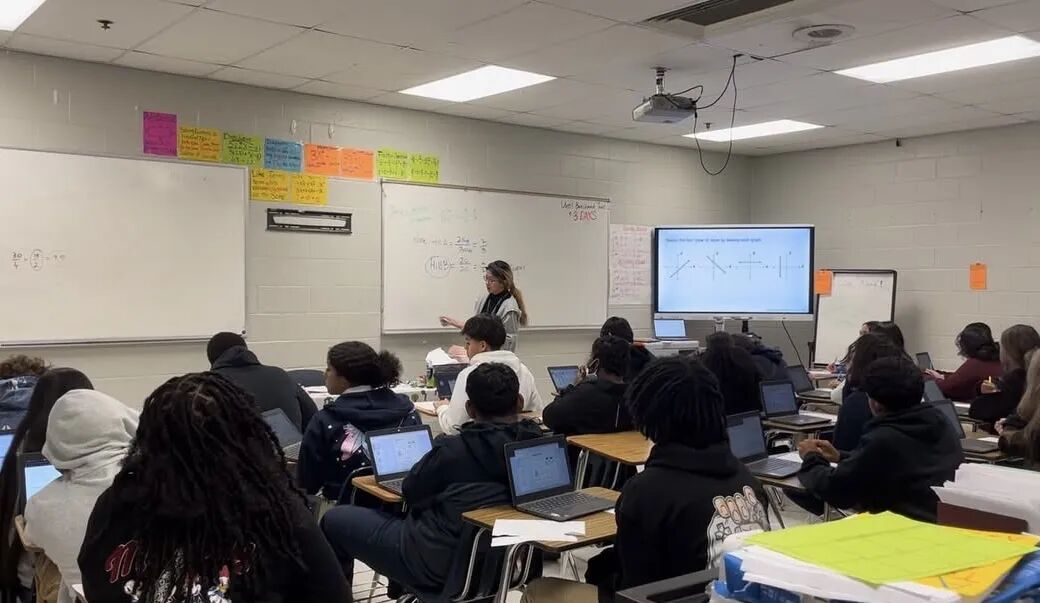

▲ Byhalia High School

What unsettled me most was not hostility, but weightlessness.

I couldn't locate myself in that classroom. My appearance, my language, my life experience, everything about me marked a difference. I did not belong to their world, yet I was expected to stand in front of it and be "teacher."

So I clung tightly to the authority that came with the role.

In training sessions, veteran educators emphasized the discipline ladder, five escalating levels of consequence. At that stage, it felt like a lifeline. Students could challenge Ms. Lu, but they couldn't easily challenge the rules posted on the wall. As long as I followed procedures, I could tell myself I had done nothing wrong.

But the cost accumulated quietly.

Step by step, I drifted farther from people, from my students and from my own sense of self.

The breakdown arrived quietly.

One afternoon, I closed the classroom door, sat down amid the hum of the air conditioner and cried, suddenly, without warning.

▲ My classroom

When the tears finally exhausted themselves, I stopped searching for excuses. I no longer blamed students for being "disrespectful," and I stopped expecting disciplinary systems to manage children for me.

The pattern was clear. The more referrals I sent, the sharper the conflicts became. I had reached a dead end. If I kept going this way, how was I supposed to survive? And how was I supposed to teach?

That night, I opened my journal and replayed every emotional explosion. Not to decide who was right or wrong, but to ask a harder question:

In the same situation, did I have any other choices?

When I slowed down enough to listen, I began to notice what I had missed. Those moments I labeled "unreasonable" were often signals: frustration, fear, hunger, exhaustion, or a simple need to be seen.

Gradually, my thinking shifted.

From They're being outrageous to Maybe, before punishment, I can give them a chance to speak.

The Hall Conferences

That Changed Everything

The next day, I asked several students involved in the most intense conflicts to step into a quiet corner of the hallway.

I didn't raise my voice. I didn't bring a referral form. I left my clipboard behind.

I brought only questions.

I spoke first with the boys who had thrown paper balls at my back.

"Do you know why I asked you to step outside?" I asked.

"I don't care," one of them shrugged, leaning against the wall. His eyes slid past me, fixed on the far end of the corridor.

I tried again.

"If I were you," I said, "and you were me, and I kept throwing things at your back, how would that feel?"

He didn't answer at first. After a long silence, he slowly straightened and stared at the tips of his shoes.

"I guess I'd be mad."

"I'm actually not mad," I told him, meeting his eyes. "I'm sad."

His gaze snapped back, startled, almost embarrassed. For a moment, it was as if he had just realized the person in front of him was not a symbol, but a human being. His eyes reddened.

"I'm sorry, Ms. Lu," he said. "I won't do it again. I just thought it was funny."

With the girl who had stormed out, I didn't begin with "What you did was disrespectful." I took a breath and tried something else.

"Yesterday, neither of us was happy," I said. "But today is a new day. I really want you to learn things in this room that will actually be useful to you."

I paused.

"If you urgently need to use the bathroom, could you wait until I finish the first twenty minutes of instruction and then raise your hand to let me know? I don't want you to miss something important."

She didn't respond. Her head stayed down.

But slowly, the backpack on her shoulders slid onto the back of her chair, the first time I had seen her take it off completely.

With the girl who had accused me of not knowing how to teach, I tried a different approach again.

"Thank you for telling me you couldn't follow my explanation," I said. "If you hadn't said anything, I might have assumed everything was fine, while you and your classmates were learning nothing. That would be the last thing I want."

Then I made a request.

"Can you help me?" I asked. "From now on, when you feel lost, raise your hand and tell me. Let's figure out together how to make this class better."

She nodded.

In those hallway conversations, my focus shifted.

I stopped defending my authority. I started looking directly at the students in front of me.

Rules became boundaries, not armor I hid behind. Above those boundaries, there was room for empathy, negotiation and trust.

I still enforced the basic rule of allowing only one student out at a time. But I stopped measuring students' physical needs by a fixed quota of bathroom passes.

Bathroom issues stopped disrupting class.

Students began yielding turns voluntarily. They watched out for one another in small, quiet ways: passing signals, whispered reminders, shared patience.

When I treated them as people with judgment and needs, they began to act like it.

Entering Their Lives,

Learning to See Clearly

Real change didn't happen only in the hallway.

It happened in the way I began to see my students and myself.

I once believed I had entered that windowless classroom carrying a torch of idealism, ready to light the way for others. Looking back, I can admit something harder.

When paper balls struck my back and words cut sharply, life stripped away my filters. It forced me to confront a version of myself that was neither as noble nor as resilient as I had imagined.

I learned to place a buffer between my emotions and my actions.

Not by suppressing what I felt or becoming emotionally distant, but by creating a pause, a protected space where I could admit to myself, I feel offended right now, without letting that feeling decide my next move.

That pause allowed me to see the student in front of me before defending myself and to choose my response with intention rather than impulse.

One boy carried the label "problem student."

One afternoon, he tossed a piece of gum halfway across the room to a friend again.

I didn't shout. I smiled, met his eyes and said, "You're someone who likes to share. It's kind of you."

It was the first time he smiled at me.

Another day, a student casually threw an assignment I had returned, one that needed corrections, onto the floor.

I didn't react to the insult. I asked him to step outside and said quietly, "Did something happen today?"

From that day on, no matter how sour his mood was, he completed his error corrections carefully.

These moments pulled me back from self-pity and frustration to the core of education.

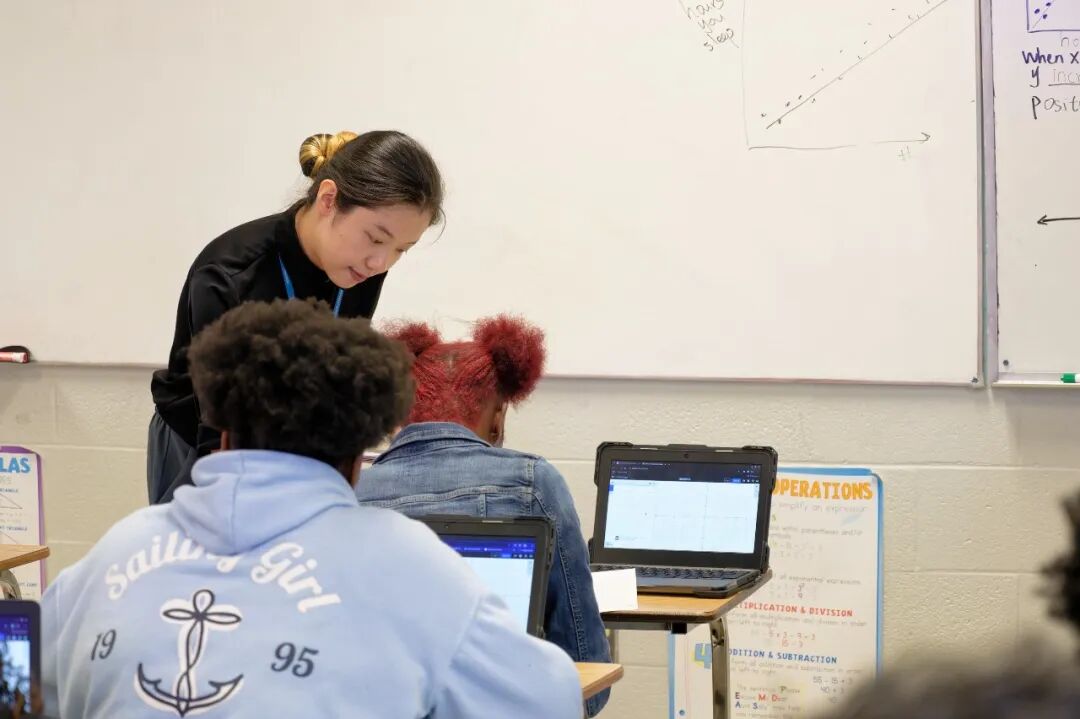

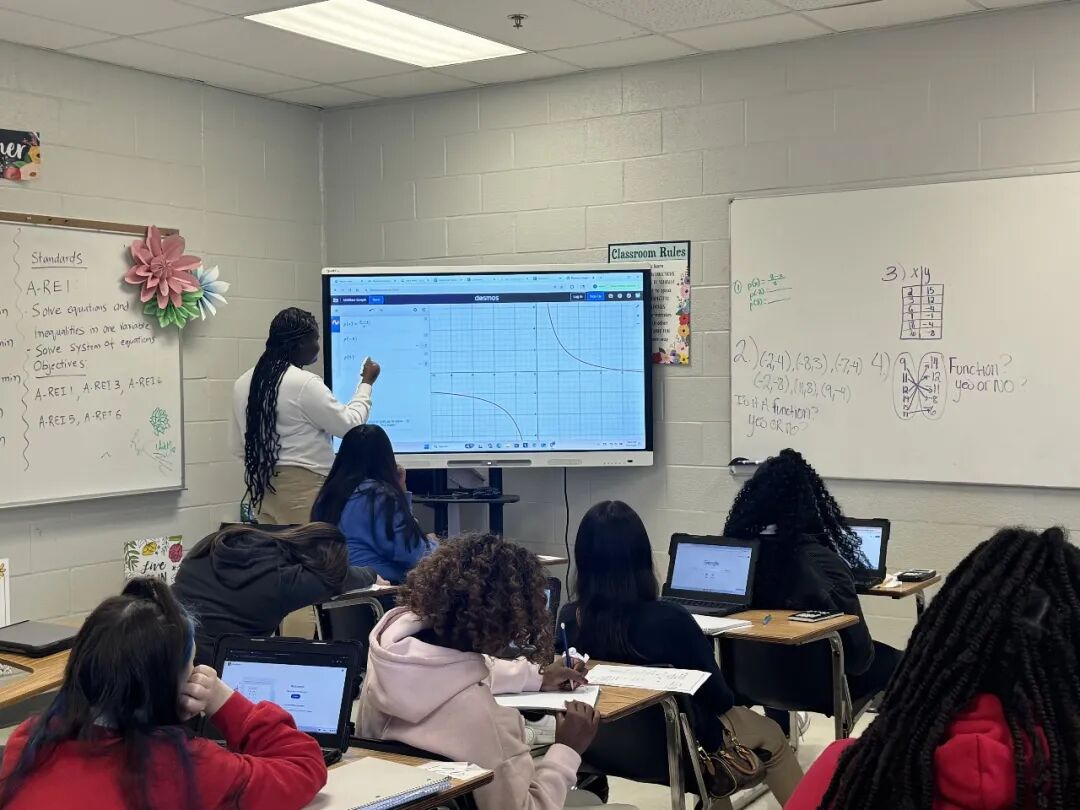

I began inviting students to become teachers.

I gave them five minutes to review a concept. Then I asked them to explain it to the class. I took photos of them standing at the front of the room and sent them to their parents.

Before long, I understood what they craved most: the chance to be seen as capable, and the chance to be listened to.

▲ Inviting my students to become teachers

To protect that space, I made one rule non-negotiable: no mocking. The courage to ask, to try, to be wrong in public, that courage is already progress.

I also rebuilt the ninety-five-minute block into something structured and clear.

The first twenty minutes belonged to core instruction, simple language, repeated until heads nodded. The rest of the block opened into peer demonstrations, group work and independent practice: time to move, speak, test ideas and rebuild confidence.

Structure created safety. Safety created participation.

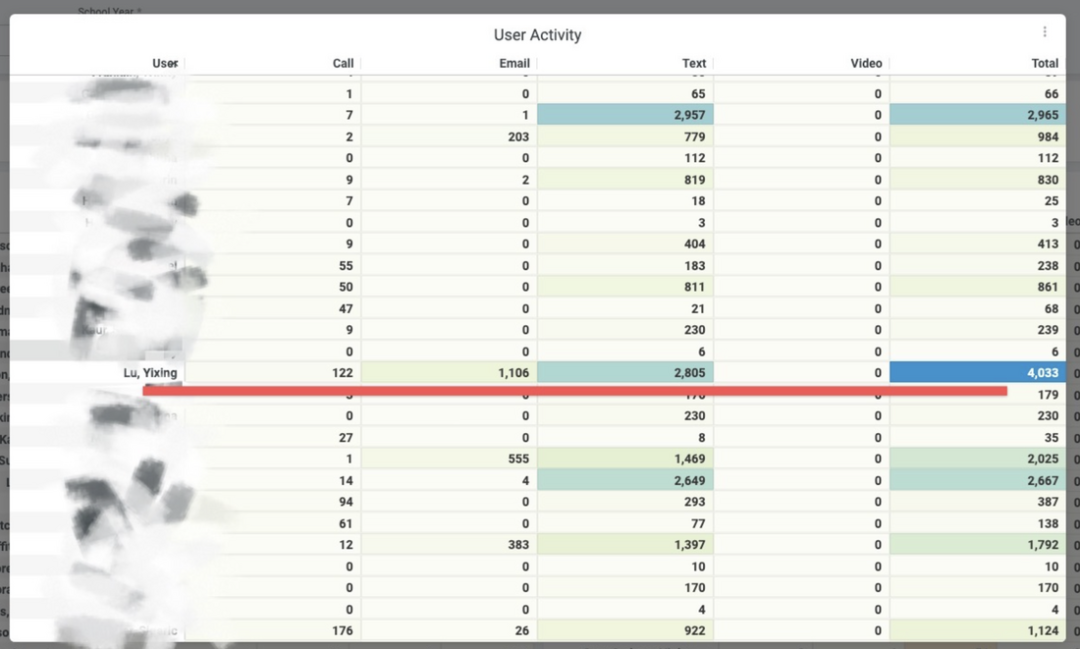

▲ My records of family contacts

during my first year of teaching

And I began paying attention to life outside the room.

In my first year, I logged more than four thousand family contacts: calls, texts and in-person parent conferences. Even with the most challenging students, I sent positive messages home first.

Those steady, genuine connections slowly reshaped how families saw math class, and how students saw themselves inside it.

Over time, realities emerged that I hadn't seen as a newcomer: students falling asleep because they worked late-night shifts; blank assignments not from laziness, but from homes without stable electricity; sharp-tongued teenagers who had never known consistent care, long accustomed to being labeled "problem students" and sent repeatedly to in-school suspension.

When I let go of the posture of a "manager" and began asking a simpler question, What's going on with you?, I finally saw them clearly.

They were not entries in a behavior log.

They were lives trying to grow through the cracks of reality.

And in their eyes, I began to see myself too, the version of me who arrived believing I would change others, only to realize I was being changed by them.

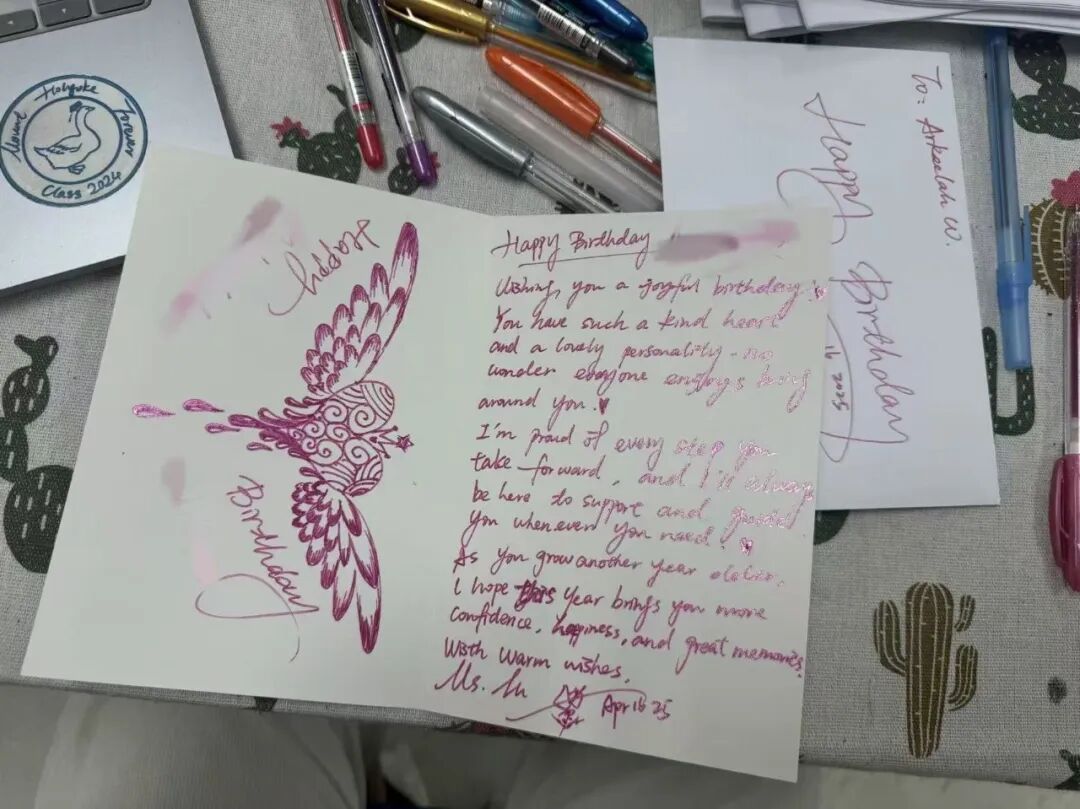

▲ I always prepare greeting cards for my students on their birthdays

Today, when I step back into that windowless classroom, I no longer see a prison.

I understand now that windows do not have to be built into walls. They can open inside the heart.

Mars is still Mars. The world around me has not softened. The roads remain without sidewalks, and the small viewing hole in the classroom door is still unblinking. But between my students and me, an invisible window has opened.

Through it, we are no longer strangers standing guard against one another. We are a community learning to grow side by side on land that once felt barren.

I am now in my second year of teaching.

What moves me most is this: when students from last year pass my classroom, they call out to the younger ones by name and say, "You better take good care of Ms. Lu."

▲ At this year's Homecoming at school, the ninth graders I teach deliberately chose "China" as the theme for their decorations. They said they hoped this would make me feel less homesick.

The Oneness of Knowing and Doing

Looking back, I understand that what UWC Changshu China taught us as Zhi Xing He Yi, the oneness of knowing and doing, was never meant to be a slogan. It was a practice. A road that only becomes real when you walk it, again and again, through the mess of ordinary life.

That is why I continue to choose paths that pull me beyond comfort. Growth, I have learned, rarely arrives as a dramatic breakthrough. It takes shape through quieter decisions, the choice to keep testing the edges of who you are, even when certainty feels far away.

At UWC, creativity and action filled the air. When students noticed a group that needed care, our instinct was rarely to sit back and debate abstract solutions. We asked a simpler question: What can I do? And then someone acted.

Joining PVO Zhi Xing, an online teaching volunteer group, was the first time that principle moved from theory into my body. I wasn't changing the world with a grand plan. I prepared lessons late at night. I showed up on a screen to teach children I had never met, in places I had never been. Through repetition, I learned something no theory had taught me: small actions leave real marks. Action itself carries meaning.

▲ In 2019, PVO Zhi Xing gave lessons to the children in the village school. The photo was taken by the village school teacher.

UWC also reshaped me in a deeper way. It made cross-cultural adaptability, and the habit of looking past stereotypes toward the complexity of real lives, part of how I understand myself. It is something I carry into every room I enter.

I came from China's national curriculum, and my English was far from fluent. At UWC Changshu, I widened my world one classroom contribution at a time. Each time I pushed myself to speak, fear loosened its grip by a single thread.

At the same time, the campus's grounding in Chinese culture anchored me as I reached outward. With friends, I sang Peking opera on the CCE stage. In Chinese HL, we read history and recited poetry. We shared tea by Kun Cheng Lake and ate mushroom oil noodles at Xingfu Temple on Yushan Mountain, talking quietly about Zen.

▲ In 2019, I sang Peking Opera with my friends on the CCE stage.

UWC taught me this: going out into the world is not a way of abandoning your roots. It is a way of returning to them with clearer eyes, learning what it means to begin from China and still face a global horizon.

That grounding mattered when Mississippi confronted me with isolation, its bluntness, its emptiness, its moments that brought me close to breaking. My inner world did not collapse alongside the outer one.

Instead, it kept drawing me, quietly but insistently, toward older intellectual lights: the Confucian pursuit of ultimate goodness; Laozi's vision of supreme goodness as water; the Chan Buddhist commitment to transcending dualistic distinctions; and Yangming Wang's insistence that moral knowledge must be realized through action. These ideas did not erase pain. They made it survivable. They became small, steady lamps, enough to keep me moving through the wreckage until something in me could grow again.

Without realizing it at first, I began offering that resilience to my students, not as a speech or a lesson, but as a presence. A way of remaining soft without becoming weak.

▲ My House-Heimat

What UWC ultimately gave me was not only education. It gave me trust, cross-cultural, unconditional and quietly practical.

When I decided to go to Mississippi, the elders around me worried most. They searched for poverty statistics, safety reports and stories of struggling schools. Their conclusion was consistent: danger, risk, unnecessary hardship. I understood their concern. But I could hear my own voice more clearly.

UWC's cross-cultural training, alongside my study of history at Mount Holyoke and my work in oral history, had formed a habit in me: behind every grand narrative, look for the living person.

▲ A group photo of my roommate and me on UWC Day in 2019.

War, religion, colonialism, national policy, I learned that what matters most to me is not abstract structure, but the lives submerged beneath it.

Once I admitted that, the path forward became clear. Whatever I did next had to involve a deep, sustained connection with real people.

So when others worried, I felt an unexpected calm. This was not an impulse. It was a deliberate response to something like a calling. I wanted to go where I was most needed, and where I could be most thoroughly shaped, to see how people actually live, far from the center.

▲ My advisory group

I have always believed this: when you are clear about who you are, a path forms beneath your feet.

In the near term, I will fulfill my commitment with the Mississippi Teacher Corps in Byhalia while completing my Master of Arts in Teaching at the University of Mississippi. I will continue to refine my practice, to make it steadier, more rigorous, and more deeply grounded in classroom reality.

Over the longer term, I hope to influence more students through what the Chinese tradition describes as teaching without loud instruction, an approach that attends not only to academic learning, but to the formation of the whole person.

Whether by remaining in the classroom, by building bridges of cross-cultural education between China and the United States, or by living more fully into the conviction that first drew me to UWC, I believe education can unite people across cultures and become a force for peace and a more sustainable future.

-End-