Walking into the Uncharted, Knowing How to Move

Issue date:2025-05-26

On a chessboard, every move follows a clear logic of rules, outcomes, and control. William Ding, once a professional youth chess player, learned to approach problems through precision and calculation, building linear paths to victory in a world of black and white. But when his gaze moved beyond the board, the world revealed itself as far more ambiguous. Faced with questions that offered no fixed answers, he found himself in unfamiliar territory: how do you engage with problems that can’t be solved in the usual sense—only understood, responded to, and lived through?

Over three years at UWC Changshu China, William gradually shifted from simulating the world through abstract reasoning to participating in it with critical awareness and deliberate action. Guided by plural perspectives, he moved from individual thought to community dialogue, from theoretical frameworks to field research, from intellectual solitude to shared experimentation. How does confusion become a form of empathy? How does personal growth align with public responsibility? In following his path—from the structure of chess to the complexity of lived systems—we begin to see not a clean transition, but a process: slow, unfinished, and deeply human.

Choosing a world I couldn't yet see

"Human beings fear the unknown the most."

I used to be a professional youth chess player.

The board seemed finite, but every match contained infinite variables. I grew up in a world of rules, clear moves and binary outcomes. In that world, precision brought control, and control brought success. I played to win. For a while, I thought that was enough.

Participating in the FIDE World Youth Chess Championship (Greece),

I am the first person on the right.

Then came the question I couldn't quite name:

What if the world outside the board wasn't black and white? What if meaning wasn't something to be calculated, but something to be asked through people, through values, through something less visible than logic?

That question didn't come with an answer. It came like a seed, quiet, unnamed, but slowly pressing to grow.

The first time I heard of UWC was on my school bus. An elder student sitting in front of me was heading to UWC in Japan. He described it as "a school that doesn't feel like a school."

Later that evening, I looked up UWC Changshu. The homepage showed students from all over the world running in white T-shirts, covered in colored powder. I didn't know what it was—an event? a ritual?—but something hit me:

There exists a kind of school where this counts as learning. Where culture doesn't divide, and presence itself carries meaning. Only later did I learn that the photo was from something called the "Colour Run."

I turned to my best friend and said, "Let's give this a try." We gave up the school we had originally planned to attend and applied to UWC together. Looking back, it wasn't a logical decision at that time. There were no pros-and-cons lists, no carefully weighted trade-offs. But that decision to walk toward something I couldn't fully anticipate was the first time I truly stepped into the unknown.

When learning stops being about solving, and starts being about seeing

I first realized that learning isn't just about "getting it." It's about ignition. That realization didn't come from a big moment; it came in the middle of an ordinary class.

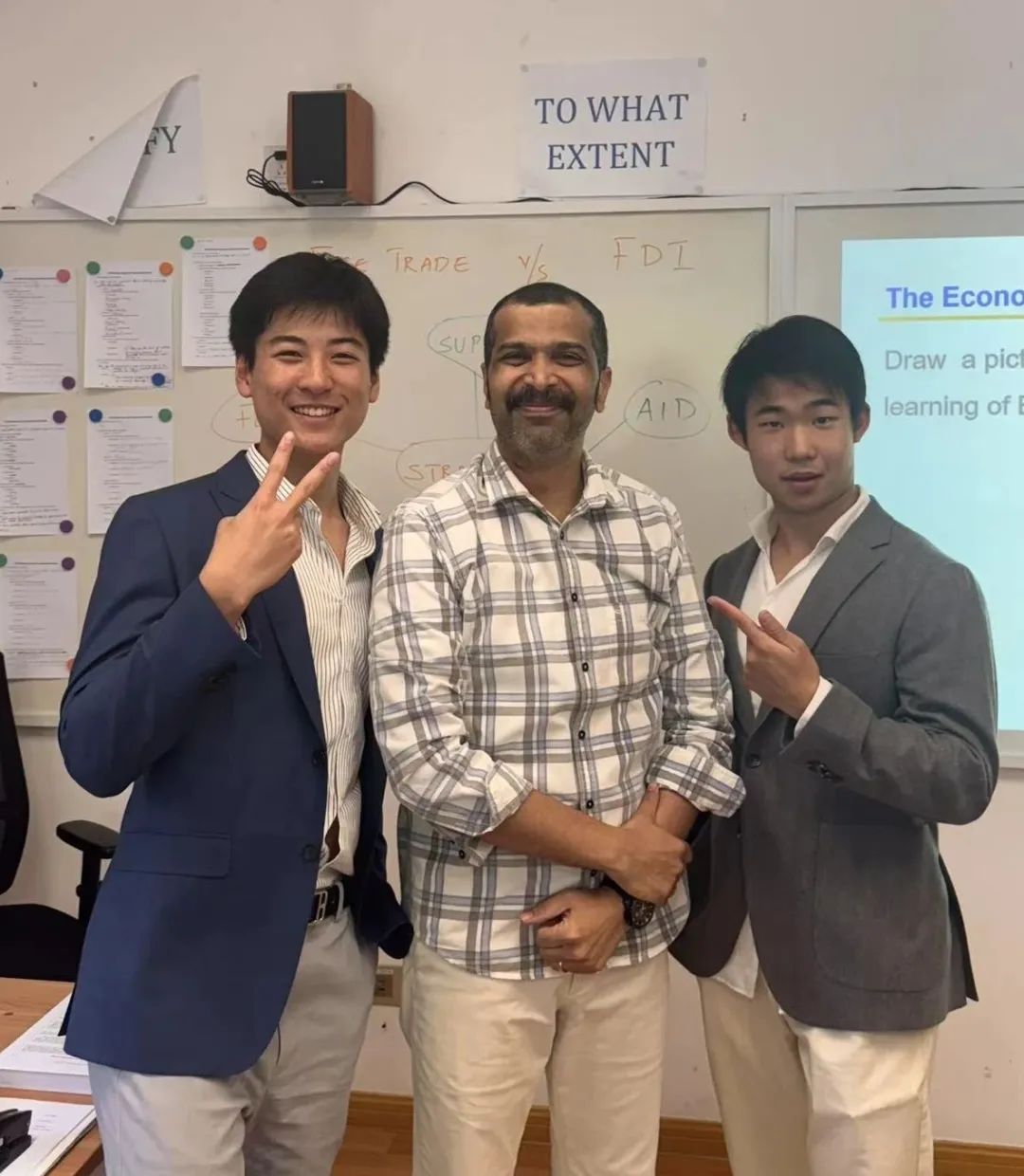

On the first day of DP1 economics, Justin asked us what we thought "economics" was. I was sitting in the middle of the room. I gave a scattered response, something about resource allocation, sustainability, and neoliberalism. It obviously had no structure, and I knew it wasn't clear.

Justin didn't correct me. He listened, then said, "None of what you said is connected yet. But you're trying to connect these ideas, and that matters more than you think." That moment startled me. He wasn't looking for an answer, but he was looking at how a person thinks.

A few months later, after class, I stayed back to talk. We started with economies of scale, then drifted to organizational efficiency. At one point, he asked me, "Do you think complexity and efficiency follow a linear relationship?" I hesitated. He started telling me about the breakup of China's telecom giants, about why TSMC doesn't design chips and why Nvidia doesn't own foundries.

"It's not about technology," he said. "It's about boundaries. Scale doesn't guarantee efficiency. Boundaries do." We talked until just before dinner. On my walk back to the dorm, my head kept echoing with that one word: boundary.

Photo taken in the last class of DP2 with Justin

After that, my notes became messier, yet fuller. I started reading the sources he recommended, researching policies, and writing reflections. One day in the library, I picked up a book he recommended, remembering its cover page on a poster stuck on the wall of his classroom: The Limits to Growth. A 1972 report by MIT's System Dynamics Group used mathematical models to track how population, resources, industry, and food might interact over time. Its claim was stark: if the current model of exponential growth continued, modern civilization could hit collapse by the mid-21st century.

I wasn't just reading data. I was confronting an idea I had never questioned: that "growth" itself could be a problem. That fire to think longer and look deeper started spreading.

And then it sparked again in a completely different classroom. In DP1 Chinese, when most students focused on exam strategies for Paper 1, our teacher, Jacky, led us elsewhere. He took us into the interior of language into news, commentary, essays, and fiction. He taught us to hear tone, feel ambiguity, and listen for what wasn't said.

"Strengthen your sensitivity to the text," he'd repeat.

Since then, I've started every morning the same way: reading the news for half an hour. Anything—politics, entertainment, opinion columns, city issues. I no longer pick based on topic. I just want to stay perceptive to the emotions behind language, the context behind events, the tension inside framing.

With my Chinese teacher Jacky

Looking back, it started small, like a struck match. But that spark taught me something crucial: a person can be moved deeply, instinctively, by a question, a sentence, or a line of thought they don't fully understand yet. And that's enough reason to keep walking. Not to get the answer, but because there's something real waiting on the other side of not knowing.

Understanding reality means stepping into it, not observing from the edge

At UWC, I slowly began to understand that knowledge isn't just for understanding yourself. It's about your relationship with the world. I started to feel a kind of responsibility, not one that was assigned to me, but one that emerged from my own questions.

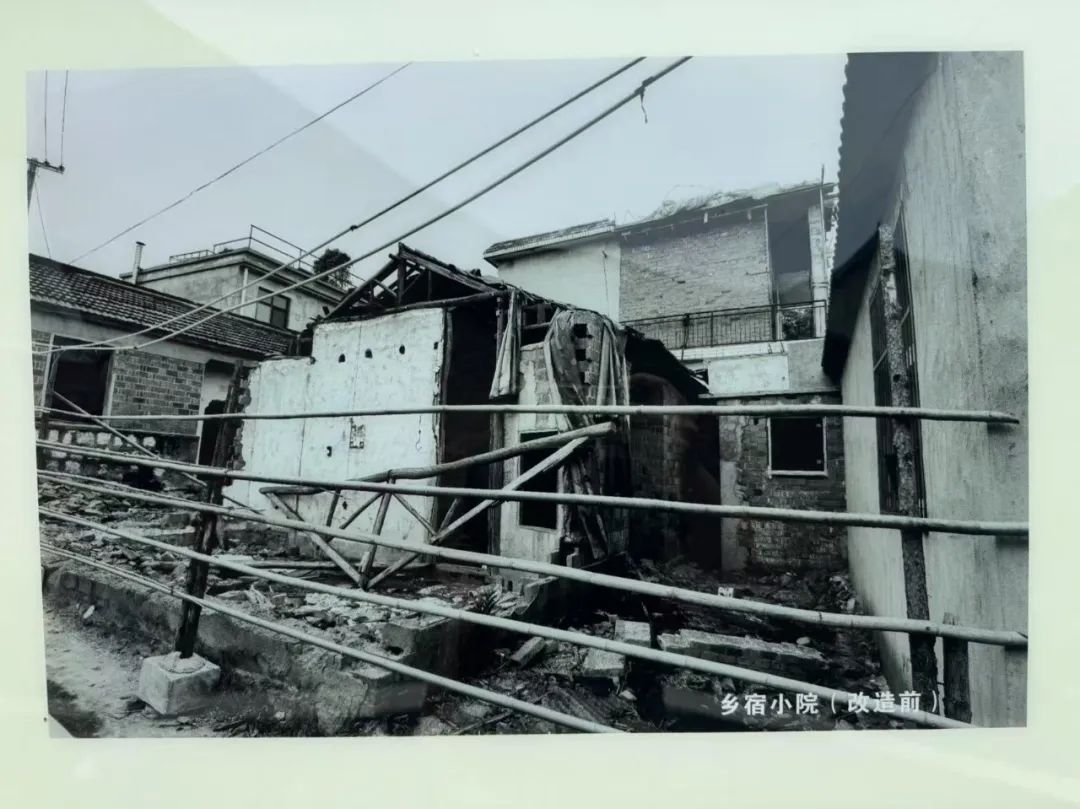

Project Week was my first step outside the classroom to see if my learning could hold up in a real-world setting. It wasn't a simulation. It wasn't a performance. It was showing up in a place where things don't run on theory, and still choosing to participate.

DP1 Project Week

My DP1 Project Week took me to Siyuan Primary School in Taiqian County, Henan Province. A rural boarding school with mostly left-behind children, it was where our multicultural team taught cross-cultural classes to students from Grades 1 to 5. We shared traditions from different countries, taught them Kenyan tribal dances, played games, drew pictures, played football and basketball.

Every afternoon, they'd crowd around us with questions. Where are your friends from? Does it snow in your country? Will you come back next year?

It was the first time I realized: education isn't just transmission—it's connection. Even a week of honest presence can become a bright part of someone’s memory.

During DP2 Project Week, my group and I worked on a script

In DP2, we went to a rural town in Guangdong and set up a drama lab for mainly primary and early middle school students. The boys in my group were in sixth and seventh grade, and most had never been on stage. Some said it was "embarrassing." We spent a whole day doing improvisation and roleplay until they began to relax.

Eventually, we co-created a version of Little Red Riding Hood—where the wolf wasn't evil, just misunderstood.

On performance day, one boy forgot his lines. He panicked. But no one laughed. His teammates guided him back on track. It wasn't about "putting on a show." It was about building a world where they could say what they needed to say.

One boy, whose name was Zidi, came up to me afterward and whispered that he wanted to go to high school in town. His dream was to become a doctor, like his sister. In his grade, most students ended up in vocational school. His sister was the only college student from their village.

He didn't look up as he spoke, but I could see that flicker of "maybe it's still possible."

That was the moment I realized that education isn't about shaping someone into something. It's about giving them the space to believe: I have something to say. I have somewhere I want to go.

After that Project Week, a few questions haunted me: What happens when we leave? What does "ordinary life" look like for these kids, once the "non-routine" ends? Do their communities have enough support? Will their paths narrow before they ever get to choose?

That summer, I spent six weeks in rural Anhui, my home province, doing ethnographic research. The idea came from Justin's class, specifically from a book recommendation from his class, Doughnut Economics. It shifted my view:

Growth isn't always the goal. Maybe the more important question is what's enough, and for whom.

From the high-speed train station in Hefei, the city looks unstoppable. But along the highway toward the countryside, the view changes: Abandoned housing lots. Closed-down schools. Elderly people working alone in the fields.

These villages weren't just shrinking. They were becoming hollow. I moved into several villages, carried a recorder and interview notes, and spoke with elders, local officials, and young people home for the summer. They told me about subsidies, relocation plans, and the old ancestral homes no one lives in anymore—but no one wants to sell. I organized my notes into case files and gave a copy to every local committee I visited.

But I didn't want to stop at observation.

I reached out to professors—some abroad, some based in China with a focus on rural governance—and we started drafting possible interventions:

1.Small mutual-aid groups based on kinship ties;

2.Community-based WeChat tools combined with GIS data for real-time support and info-sharing;

3.Pilot models that restructured land-use rights to help migrants retain partial economic benefit from their farmland.

I wrote each proposal into a report and revised it with village officials. Some got tested. Others were shelved, waiting for the right moment. The deeper I went, the more I understood that some problems don't yield to effort. They're structurally rooted in resource flows, policy design, and local execution capacity. But that doesn't mean you stop, it just means you go slower and deeper.

Connection begins with action; change begins with mutual understanding

Back on campus, I kept building things. Not because they were part of a plan, but because they felt worth doing.

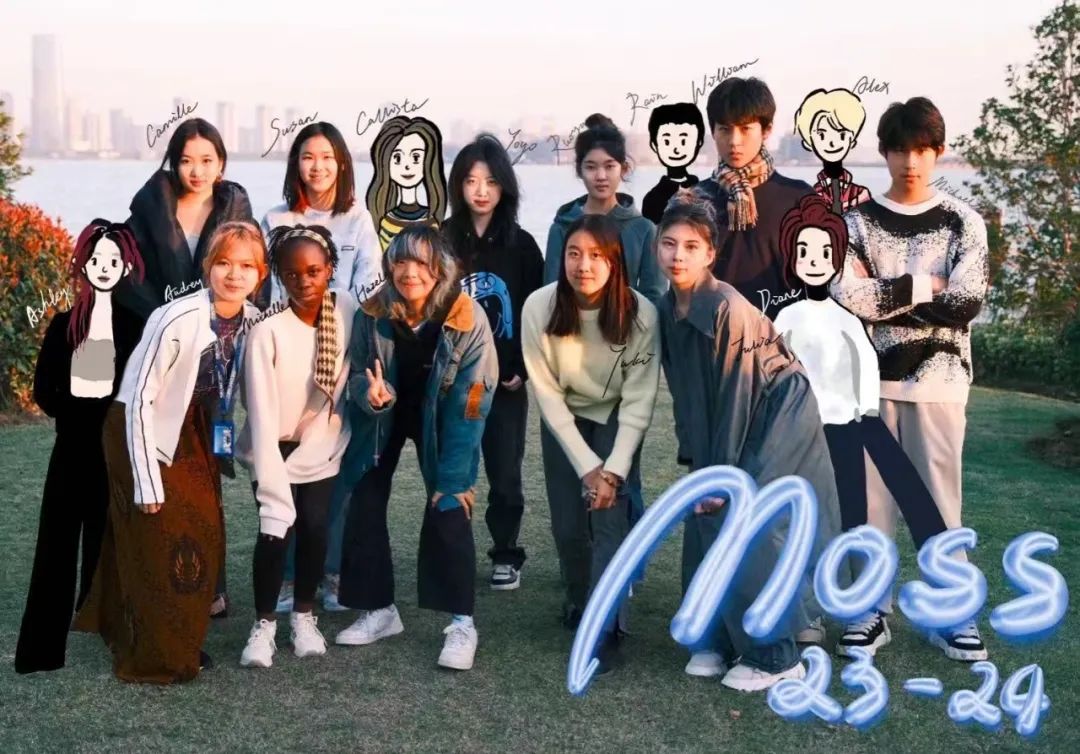

In FP, I co-founded MOSS, a biodesign club focused on sustainable materials. It started with a simple question: how might people live sustainably on Earth, not just today, but for the long term?

MOSS at Zhi Xing Fair

We experimented with sodium alginate to make algae-based fabric: soft, lightweight, and biodegradable. The material could be used for bags, clothing, and light decor. We weren't designing for markets. We were testing how materials themselves could carry ideas, how form could hold meaning. And soon, others joined in. More students began reading, prototyping, and tracing their own questions through materials.

MOSS team

In DP1, I co-founded the Chess Club with a friend. It was the first semester after international students returned post-COVID, and we wanted to build something that didn't depend on language.

We started with 19 students from a mix of backgrounds. We taught basics, organized friendly tournaments, and left space for people to just play. We used Victor's math classroom—tables pushed together, different languages echoing across the board. One student, who had barely spoken to anyone in the first few weeks, started staying after sessions. Eventually, he began inviting others to play.

He once told me, "On the chessboard, you don't need to say everything fast. You just make your next move. And somehow, people understand." For him, that was the first place on campus that felt like it didn't require translation.

Climbing with friends

Outside clubs, I kept a few other constants. I was part of the school cycling team, circling Kun Cheng Lake every Wednesday. I helped younger students in economics as a peer tutor. And when I could, I climbed mountains.

The path doesn't reveal itself at the start—it takes walking

The moment I realized something in me had quietly taken root came on a quiet afternoon, just after my DP2 physics exam.

I had lunch with Jacky. It was supposed to be a short meal—just a check-in to some extent. But it turned into a two-hour conversation. We talked about everything: ancient texts, writing styles, and what people mean when they talk about growing up.

He didn't offer advice. He asked questions. He took his time. It felt less like a conversation and more like slowly unwrapping a thought together.

At one point, he said, "In Chinese philosophy, we believe that who you are—your temperament, your inner compass—is something you're born with. It's already in you. Education isn't supposed to overwrite that. It's supposed to help you recognize it. To help you live in alignment with it."

That stayed with me. I didn't have a perfect reply. But something clicked.

I began to see how all the pieces—field notes from the villages, post-class conversations, morning newspapers, the silence of walking alone with a recorder—weren't fragments. They were forming a line. Not a roadmap or a career plan, but something quieter. Something like a direction.

UWC didn't give me a fixed path.

It didn't assign right or wrong answers. It didn't wrap growth inside a fixed set of values.

What it gave me was the ability to keep moving forward even when I don't know what's ahead. The courage to pause, to go deeper, to stay with uncertainty. And over time, that became a kind of freedom—

To choose when to dig in.

To choose when to wait.

To choose not to look away.

And to keep faith with a future that hasn't yet arrived.

This fall, I'll begin my undergraduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania. That blue Penn T-shirt I hung on the dorm wall during the Foundation Program, and the same T-shirt is still hanging on my bed now. It was more than decoration. It was a quiet promise I made to myself. That hasn't changed in three years.

At Penn, I plan to study mathematics and business economics & public policy. I'm especially drawn to questions that live at the intersection of theory and structure—things like modeling, institutional design, and development economics. I want to understand how logic informs rules, and how power flows beneath them. I want to carry forward the habits of thinking and action UWC helped me build—and bring them into a world that's far more real and complex than anything we simulate in school.

And I think that's how most paths work.

They don't begin with clarity. Like every mountain I've climbed, they start wide and slow, full of switchbacks and steep ridges, sometimes no summit in sight. But if you don't retreat, if you don't rush to go around, if you stay just a little longer, just a little deeper, eventually, a trail appears beneath your feet.

It wasn't there before. But now it is. Because you walked it.

Like the final line of The Count of Monte Cristo, a sentence I've always loved--

"Wait and hope."

Article and photos:William Ding,Class of 2025,UWC Changshu China; Class of 2029, University of Pennsylvania.