On Idealism's Island: Redefining Education as a World Player

Issue date:2025-05-15

Three years ago, Isabella Wang arrived at UWC Changshu China, brimming with idealism and eager to embark on a journey of exploration and growth. She embraced every challenge with enthusiasm, diving into new activities and courses. Through debating, she gained the courage to express her beliefs; through philosophy, she developed ways of thinking that bridged diverse subjects; and as a student representative, she participated in the UWC International Congress.

While some of her peers were stressed by the competitive nature of school, Isabella saw herself as a "world player" and founded a nonprofit called Universe Memoir to inspire others to recognize life's endless possibilities. Now, as she prepares to bring her UWC experiences to university, her story illustrates a key point: when education provides space for free and even seemingly "impractical" explorations, it allows the seeds of idealism to flourish through genuine discovery. This empowers everyone to become the "world player" in their own life story.

Drifting, Reshaping on an Island of Idealism

I first came to UWC driven by idealism. Its vision of education — empowering students to explore themselves and change the world — deeply resonated with my own. I wanted high school to be more than academics. I longed for interdisciplinary exploration, for experimenting with seemingly impractical, whimsical ideas, and for something more. Thus, although I had offers from several international schools, I ultimately chose UWC, and landed on this small, serene island in Changshu.

It was also my first experience living independently in a residential setting. Sharing life with peers from over 100 countries and engaging with students across the 18 UWC campuses made for a high school experience like no other.My most significant growth moments didn’t happen in classrooms; they unfolded in rich, diverse experiences and conversations with people.

I picked up the ruan, a traditional Chinese instrument, during a China Band open session. I learned archery through Zhi Xing. I played snooker with friends in the Common Room, organized the annual TEDx event, and debated for the first time during the Chinese Debate Zhi Xing taster and later won Best Debater and the championship at the FP Chinese Debate Tournament.

I studied film, design technology, and philosophy for the first time. During cultural weeks, I savored cuisines from around the world, picnicked on the Grass Circle, wandered under moonlight to Yushan Academy, and stayed up chatting by the lakeside steps until curfew. These experiences gave me countless unforgettable memories.

Learning the ruan in the China Band open session

Learning the ruan in the China Band open session

During archery Zhi Xing

During archery Zhi Xing

I shared my reflections on the

2024 TEDxUWCChangshu event in this video.

Before coming to UWC, in unfamiliar settings, I preferred observing before speaking, and planning before acting. But here, I gradually embraced a different way of living — one that welcomes spontaneity, embraces uncertainty, and values action as a form of thought.I realized that one doesn’t need perfect knowledge to begin something, or airtight logic to express a view. Sometimes, the act of doing reveals insights that thinking alone cannot.

One experience I cherish most is preparing for the FP Chinese Debate Tournament. It was a time of pure thinking, reading, and discussion. We spent whole afternoons and evenings dissecting single debate topics — going beyond the first seemingly "correct" answer to explore deeper logic. From debating whether romanticism is a spiritual trap for youth, we dug into the roots of 19th-century Romanticism and questioned the very semantics of "trap." From discussing whether literature should be read with or without the author in mind, we unearthed Roland Barthes and postmodern literary critique. These long sessions of constant argument, destruction, and reconstruction are rare in daily life. I’m lucky to have had many such moments.

As Koji Suzuki once said, "To say a flower is beautiful invites someone to argue, ‘Not all flowers are beautiful.’ To preempt that by writing ‘some flowers are beautiful, and some aren’t’ — that's meaningless. Expression requires courage." In debate, absolute neutrality is the safest but least constructive stance. Through FP and Chinese debate, I learned to clarify my positions, to express them boldly, and to participate in the world — not just observe it.

Debating in the FP Chinese Debate Tournament final

Debating in the FP Chinese Debate Tournament final

"The essence of UWC is people." I’ve heard this phrase many times since arriving, and it couldn’t be truer. My most meaningful growth has come from conversations with friends — in classes, dorms, villages, and everywhere in between. These seemingly small moments shaped my sensitivity and empathy toward the world, capacities that I’ll carry for life.

UWC is famous for its diversity. While that’s often represented through statistics like "students from 127 countries", I found the deeper form of diversity lies in thought. Even students from similar places often have radically different ways of thinking due to their unique backgrounds. My philosophy teacher Max once said that at UWC, those from the most conservative upbringings often contribute most to discussions in this liberal environment as differing views create real dialogue and innovation. In today’s polarized world, such substantive diversity, coupled with rational, respectful discourse, is increasingly rare. I hope UWC will always preserve this precious space.

Project Week is another defining part of my UWC experience. In DP1, my group went to teach at Siyuan School in Xincai, Henan. As the only Chinese student in the group, I took on the main role of facilitating lessons. Living there, we got to know the students' daily lives and reflected deeply on education inequality and resource distribution in China. The teachers wholeheartedly dedicated themselves to the children, most of whose parents worked far away.

Cultural exchange in Henan for DP1 Project Week

Cultural exchange in Henan for DP1 Project Week

In DP2, we designed our own Project Week. My group chose to go to Jingdezhen to learn kintsugi (ceramic repair with gold), explore the ceramics market, and create a children’s picture book to support cultural heritage. We wandered ghost markets, chatted with artisans and vendors, and practiced kintsugi ourselves. Without this experience, I might never have spent time understanding the origin of most ceramic crafts across China — let alone their markets, supply chains, and traditions.

Practicing kintsugi in a Jingdezhen workshop for DP2 Project Week

Practicing kintsugi in a Jingdezhen workshop for DP2 Project Week

Deconstructing and Reconstructing between Disciplines

At UWC, academics are just as rich with novelty and interdisciplinary exploration as any other aspect of school life. Ever since I read Sophie's World in fifth grade, I’ve been fascinated by philosophy. Each time I dive into a philosophical text, I feel resonance that transcends time and space, realizing that my thoughts had, centuries ago, already been voiced by thinkers across the world, from Aristotle in ancient Greece to Nietzsche in Germany to Isaiah Berlin in the UK.

The Chinese writer Wang Xiaobo once described being struck with awe when watching a swallow fly into a hole in a courtyard pillar that had once belonged to a royal residence, and imagining that, hundreds of years earlier, a young palace maid might have watched the same scene. Similarly, Chen Chuncheng’s novella The Submarine at Night tells of a business man searching the open sea for a coin once thrown into it by Borges. It’s probably the same feeling when I read philosophy.

My academic interests have always been broad, and philosophy is where I find the foundational knowledge and tools that tie all disciplines together. A core skill in writing philosophy papers is evaluation: analyzing a philosopher’s argument, assessing its logic, and developing one's own position. This kind of analytical thinking helps sharpen independent reasoning and trains us to question everything, resisting the pull of cognitive biases and mental shortcuts.

Growing up, I loved detective novels, mystery films, criminal psychology. I even spent time decoding ciphers and exploring various branches of logic puzzles. One day in high school philosophy class, it struck me—my fascination with these genres stems from the same impulse that drives me toward philosophy: the joy of deconstructing constructed realities, exposing the inner machinery of logic, and pushing boundaries to reconstruct new frameworks.

In Max’s philosophy class, I encountered the Dao De Jing through Tai Chi. It was also my first experience with Chinese philosophy. It amazed me to discover that Laozi had already, more than two millennia ago, pointed to dilemmas that contemporary analytic philosophers are still struggling to untangle with modern jargon.Chinese philosophy, with its foundation in natural observation and intuitive flow, operates in a completely different dimension than continental or analytic traditions.

Learning to place each philosophy in its cultural and historical context gave me not only a deeper understanding of the ideas themselves but also a greater capacity for empathy. It trained me to understand and respect the diverse cognitive frameworks of the people I encounter—not just in theory, but in lived experience. It helped expand my lens beyond the personal and the local to a genuinely global scope.

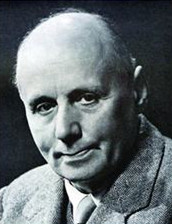

A philosophy debate on the topic of personhood through the form of mock trial,

A philosophy debate on the topic of personhood through the form of mock trial,

where Max acted as judge

This spirit of open-ended, cross-disciplinary thinking runs through all UWC courses, especially in the humanities and social sciences.In Jared’s Theory of Knowledge class, we could jump from history to philosophy to education to science through the lens of epistemology. My Chinese literature teachers, Han Lu and Pan Lei, ran their classes more like free-flowing conversations, gently sharpening our analytical intuition through dialogue. In English literature, Douglas would start with a Murakami novel and zoom out to explore postwar Japan’s psychological landscape, giving us both freedom to express and context to deepen. Sissi also brought abstract economic concepts down to earth through interactive simulations.

In the FP year, I took film and design technology, driven by a simple curiosity to try something new. Film class taught me to shift perspectives—to watch movies as a director, breaking down framing, shot language, and historical aesthetics. I even co-wrote and co-directed a short film with classmates. In the DT workshop, I picked up new hands-on skills such as modeling, welding, laser cutting, and carpentry. That year of design training sparked my passion for engineering and expanded into product design projects outside of class.

A voice-activated turtle toy I built with my partner in DT class,

A voice-activated turtle toy I built with my partner in DT class,

themed around endangered species

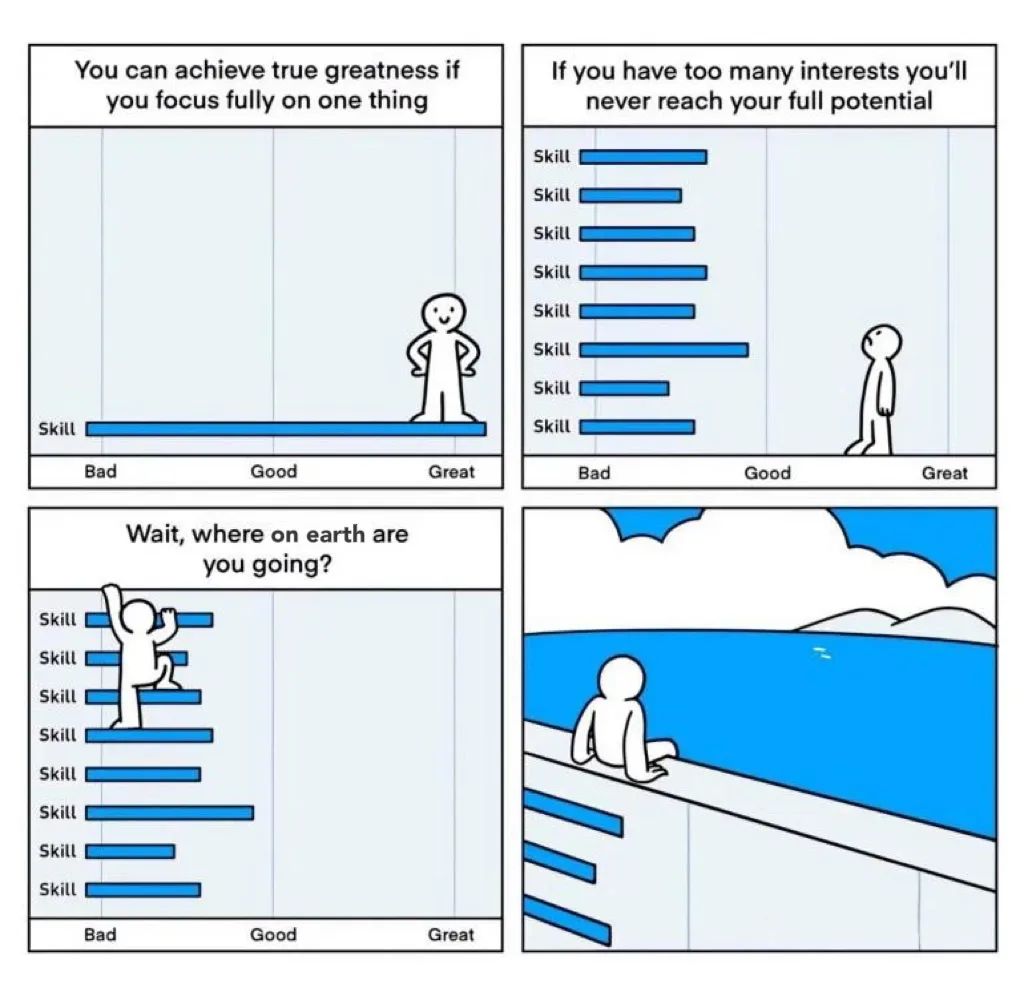

Since I’m curious about so many things, people sometimes say, "One can’t be good at everything. You need find a focus." But I’ve never fully agreed. I hope to be able to share unique insights about any topic that interests me, and at the same time, go deep enough in certain areas to bring transformative changes. In today’s age of AI and complexity, I believe it’s exactly this kind of multi-faceted thinking—this capacity to connect fields and fluidly navigate between them—that drives true innovation. And at UWC, I’ve been lucky to find the perfect space to grow this ability.

A picture I like

A picture I like

Uniting Knowledge and Action through a Global Vision

During my first year of the Diploma Programme, I had the honor of traveling to Phuket, Thailand, to attend the once-every-six-year UWC International Congress. There, I engaged in lively discussions on innovative education with teachers, student representatives from eighteen UWC campuses, and graduates spanning various industries. I met individuals such as the Indonesian Minister of Education and Culture, an alumnus of UWC in Singapore who went on to drive education reform in Indonesia; an Indian classmate who used mechanical engineering to solve water shortages in his hometown’s agriculture; and a New Zealander who travels the world advocating against war and promoting peace.

In UWC’s global community, I witnessed how real, passionate individuals from every corner of the planet and a myriad of fields unite in the pursuit of a better world. When someone shares a vision for changing the world, their words are met not with skepticism but with genuine belief in their ability to succeed.

Speaking as the CSC student representative

Speaking as the CSC student representative

at the UWC International Congress

This experience also inspired the core mission behind my founding of Universe Memoir in May 2022, a nonprofit organization aimed at helping people realize life’s boundless possibilities and to gather the resources needed to achieve their ideal lives and even change the world.I noticed that many around me felt anxious and lost, whether from uncertainty about the future, the overwhelming pressure of relentless competition, or other reasons. Much of this stemmed from a linear perception of life.

When we broaden our perspective—examining different eras, the diverse systems of countries around the world, or even looking beyond human history and our planet—we see that there is no need to be anxious about not being the best in one narrow field. Instead, we can forge new paths or simply explore all the life choices that truly interest us. This realization is what I embraced at UWC, and it’s a vision I want to share with more people.

Over the three years at UWC, I’ve grown Universe Memoir from a club in 2022 into a genuine international nonprofit, a global community of idealistic adventurers. Whether it’s our "UM Human Observations" interview series, the quarterly innovation summits, creative contests, and discussion events held in the UM Inspiration Lab, or the UM Global Think Tank that brings together diverse project resources alongside our annual education-related public service events at the UM Community Base, the expansion of our programs has solidified our core purpose. Today, Universe Memoir stands as a global empowerment platform for "world players," linking experts and organizations from all fields to support every idealist with wild ideas and a burning desire to change the world by uniting thought with action.

The "world player" spirit draws inspiration from German philosopher Friedrich Schiller’s concept of Spieltrieb, the drive to play, which I encountered while preparing a debate topic. Schiller argued that the only way to free oneself is to keep the mindset of a player. In a game, we invent our own rules; we follow them by choice rather than because they’re imposed by deities or authorities.

Viewing life as a game and ourselves as its players empowers us to imagine, invent, and create freely, rebelling against conventional discipline so that we may truly live according to our ideals. This powerful, self-determined perspective is exactly what Universe Memoir strives to nurture and what I personally hold dear: freedom, rebellion, and idealism.

Recently, we launched the UM "World Player" Creative Writing Contest with the theme "Modernity." The competition encourages young literature enthusiasts to break the boundaries of conventional writing and explore pioneering forms of expression. To provide a platform for emerging writers, we’ve partnered with a publishing house and the Hangzhou Literary Society, offering generous prizes including monetary awards and official paper certificates.

I believe that the essence of UWC is found in these subtle intersections—where theory guides action and reason intermingles with passion to form the foundation for changing the world.

The Right to Embrace Leisure

"Simply by lying down, one can possess the very essence of spring."

——Natsume Sōseki, Botchan

Enjoying spring at Grass Circle with friends

Enjoying spring at Grass Circle with friends

I’ve always held a core belief about high school: it should be a unique, artful experience that allows students the freedom to explore themselves and the world, rather than merely a transitional phase before college or a means to an end in pursuit of some grand future goal.As Kant famously advised, "Treat humanity as an end, not merely as a means." To me, high school should be valued in and of itself, not just as preparation for university. This is one of the things I love most about UWC: it fully matches my vision of high school by giving students the right to enjoy leisure.

At UWC, the curriculum and residential lifestyle afford me ample free time to explore new experiences and pursue what I genuinely want to do. I can express every whimsical thought and investigate its possibilities without being hindered by questions like, "What use is that?" Whether I’m lying on the lawn by the lake savoring the springtime birdcalls, sitting roadside in a village listening to music and discussing everything from art to contemporary literature and consumerism, or hopping on a bus with no set destination, I am actively practicing the great art of leisure.

Throughout the entire college application season in twelfth grade, I hardly felt any urgency or anxiety. The whole process unfolded naturally. I still read regularly each week, occasionally watch a film, bounce between browsers and platforms to research new ideas, and participate in a multitude of activities both on and off campus.

After all, college merely offers different possibilities for experiences. What we make of it depends solely on us. More importantly, the new people we meet and the fresh experiences we accumulate here will equip us with the resilience to overcome any challenge, the insight to contribute unique perspectives to any conversation, and the confidence to live a life true to our dreams, no matter the circumstances.

Looking ahead, I will attend the University of Pennsylvania for my undergraduate studies, aspiring to enroll in a dual degree program between the College of Arts and Sciences and Wharton.I hope to combine academic inquiry in the humanities and social sciences—ranging from philosophy and comparative literature to political science and psychology—with entrepreneurial, investment, and technological tools to transform theoretical ideals into tangible societal change. UWC’s global education on world citizenship has given me the confidence and foundation to pursue a life of impact.

-End-

Article and photos: Isabella Wang, Class of 2025, UWC Changshu China; Class of 2029, University of Pennsylvania