Interview with Dr Musimbi Kanyoro

Issue date:2025-11-27

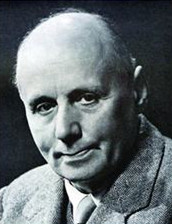

During UWC Changshu China's 10th Anniversary celebrations, we had the privilege of holding an in-depth conversation with Dr Musimbi Kanyoro, Chair of the UWC International Board.

From linguist to global leader to a guide across generations, Dr Musimbi has dedicated her life to building bridges of understanding across cultures. In this interview, she shared profound insights on UWC education in the age of AI, the nurturing of curiosity, and the role of education in fostering peace.

Musimbi Kanyoro

Chair of the UWC International Board

Musimbi Kanyoro is an accomplished leader with more than three decades of experience leading international organizations. She is the immediate past President and CEO of the Global Fund for Women. Dr Kanyoro worked for David and Lucile Packard as Director for Population and Reproductive Health. Prior to moving into Philanthropy in the USA, Kanyoro spent twenty years in Geneva, Switzerland.

Dr Musimbi Kanyoro has been Chair of the UWC International Board since 2019. She is a member of the UN Global Compact Board and serves as Senior Advisor to "Target Gender Equality". She is also the Board Chair of the Women's Learning Partnerships (WLP), and serves on the Boards of the London School of Economics (LSE) and CARE International (CI).

Kanyoro received a Ph.D in Linguistics from the University of Texas in Austin and a Doctor of Ministry (DMin) from San Francisco Theological Seminary. She was also a Visiting Scholar at Harvard Divinity in Old Testament and Hebrew Studies. Musimbi Kanyoro has held leadership positions in Research of Languages, Human Rights and Philanthropy.

Kanyoro is the recipient of numerous awards over the years including a recognition as one of the 21 Women Leaders for the 21st Century by Women's E-News. In 2015, Forbes named her as one of the 10 power brands working for gender equality and in 2016 she was recognized on a list of "Forty over 40 – women who are reinventing, and disrupting and making an impact". In 2018, she was named among the 100 people making a difference in gender policy, and in 2019 she was recognised as one of the nine people who fought for the planet alongside Bill Gates, Ban Ki-moon and Michael Bloomberg.

▲ Dr Musimbi Kanyoro delivering her speech at the

10th Anniversary Ceremony of UWC Changshu China.

1. Interviewer: Dr Kanyoro, thank you for having this conversation with us. You've spent your life building bridges: between languages as a linguist, between cultures as a global leader, and now between generations as Chair of UWC International.

Today, we hope to learn more about how these acts of connection can continue to guide UWC's mission to unite people, nations, and cultures for peace and a sustainable future. In the age of AI, what do you think is the value of UWC education?

Dr Musimbi: Thank you very much. It's really a privilege to be here at UWC Changshu in China, and to be able to talk about UWC and AI together. One of the significant things about being in China is its development of artificial intelligence, as well as other important forms of communication.

I grew up in a generation that saw the introduction of computers from the very beginning. When I did my PhD dissertation, we worked on huge computers. Today, with AI, much has changed—to the point where it is both exciting and frightening.

In this age of AI, for a movement like UWC that brings together young people from all over the world, one expectation is that they themselves will become both users and advocates of AI. They will be able to go back to their communities and introduce this important tool of communication and innovation.

I look to young people to interpret what AI means for themselves, their communities, and the world. I hope UWC students will show others the advantages of having artificial intelligence support our thinking, our work, and the way we care for the environment.

But I also hope they will show us where we should be cautious—where AI may seem more clever than human beings, and where we must think about the precautions needed to avoid risks or destructive outcomes. Large or small communities can be affected differently depending on the data used to train AI. So it is an exciting moment—full of excitement, expectation, and fears that must be managed together.

2. Interviewer: In many communities, access to AI is a luxury. What would "AI as a public good" look like?

Dr Musimbi: The first issue is access—access to knowledge, and access to both software and hardware. These determine who is able to benefit from AI. If you have hardware but not the knowledge of how to use it, especially with AI, you cannot go far. But if you also lack software or the tools needed to run AI, you will be excluded as well.

So advocacy must include access—access to knowledge, especially to the ability to manage knowledge, and access to the tools that make that knowledge possible.

Poverty and economic differences can be barriers, and so can limited exposure or fear of technological change. Many barriers can stand in our way. But I like to think about the things that enable us to use AI.

I am excited that schools are introducing AI skills. I am excited that more people are beginning to accept AI, because we cannot stop it. Instead, we should ask how we can use it for the benefit of our environment and our societies. People are already using different forms of AI in agriculture, in sharing medical knowledge, in predicting climate patterns in specific places, even in understanding groundwater levels.

There are endless ways AI can be used as a public good. But we must also be careful that it is not used in ways that cause harm.

3. Interviewer: Yes, and building on that—technology often rewards visibility. But in the UWC community, what we value most are the connections between people and between communities. Much of learning—care, kindness, patience—is invisible. How do we ensure what truly matters remains valued?

Dr Musimbi: A key value of UWC education is that it teaches young people what it means to care. I have been told that there is no AI system that can truly care. AI may be taught to express love, but it cannot love.

Human education brings something different: the caring spirit, the ability to feel with others, the ability to hold people in a good place when they are facing challenges. Challenges may be displacement—we know this because our student body includes those who have been displaced—but they may also be the joy of partnership, success, learning new things, or encountering each other.

So yes, there will be tension. Technology may help things happen faster or on a larger scale, but people give the element of humanity—love, care, empathy—and help others cross from sadness to a better place, instead of being left in loneliness, even when technology is around them.

4. Interviewer: I agree. That's why experiential learning at UWC matters—you have to connect with people from different backgrounds and cross bridges with them. With that, let's move to something more playful: curiosity, learning, and the human core. If curiosity were a renewable resource, how could schools and educators protect it?

Dr Musimbi: I don't believe curiosity is renewable in a simple sense, but I do believe curiosity can be developed.

We are born with it. When you watch a young child grow, you see how new things attract their attention. You see curiosity as they begin to ask "why"—that stage when every child asks why about everything. That is already a sign of a curious mind. And that early curiosity can grow into something even more useful—not only for personal knowledge, but for broader understanding that benefits our society.

Curiosity helps us grow new ideas. It drives innovation. It gives people scientific minds that look for evidence. And in UWC, because we always have students coming in from everywhere, curiosity is renewed through learning together and living together in a space where diversity is valued.

If we sustain this environment—of learning together, sharing together, and keeping inclusiveness at the centre—then curiosity will stay alive.

Interviewer: I agree. And I think UWC prompts us to ask more "whys"—because when we see how different we are, we also ask why we are the same.

Dr Musimbi: And yet why are we also the same in many ways? Because when we are brought together and we are thinking together, we actually discover that we have a lot in common, and we can be able to grow on that commonality.

5. Interviewer: If you were to teach the grammar of peace, what would be its verbs?

Dr Musimbi: Connect. Love. Sacrifice. Share. Imagine. Live in each other's space. Empathise. Sympathise. Care. Be passionate. Do good. Provide. Those are some of the verbs I would use.

6. Interviewer: I love that. Finally, a question about hope and inheritance: Looking back at your journey—from linguistics to global leadership—what single thread connects it all?

Dr Musimbi: I have always been connected to people. From the time I was in school, I grew up with values very similar to UWC values—caring for people. I studied in my home country and later joined the United Nations Youth as a movement, which took me to Indonesia, Singapore, the United States, and the United Kingdom when I was still very young. My graduate studies and later work continued this journey.

Throughout my life, my professions have taken me around the world. I have visited more than 150 countries, not for tourism, but to have encounters with people. Those encounters have made the biggest difference. Everything that has brought me joy—growing, learning, contributing—has come from people inviting me into their spaces.

I have also had opportunities to ask people to take part in work and to lead organisations as a CEO. These experiences give us a chance to give what we have, and also to receive so much from others.

I am grateful for the people who have influenced me—young and old, from all races, all languages, and many countries. That is where my joy has been: connecting with people.

-End-