The Lesson at UWC: How I Root and How I Float

Issue date:2025-08-22

UWC Changshu offered more than an international curriculum; it became a warm, inclusive safety net. There, Xiaoshu found the courage to organize a dialogue on the Nanjing Massacre and peacebuilding, and she built confidence and leadership through Latin dance and martial arts. Initially fearing she might lose touch with her Chinese identity, she discovered, “The reality was the opposite—surrounded by diverse cultures, I came to see my roots more clearly.”

Her three years at UWC Changshu transformed self-doubt into self-discovery, giving her the space to embrace her authentic self and the confidence to engage with the wider world.

In the Language and Culture class in DP1, we started to discuss the term “language ideology.” I told my teacher, Yarina, about my “Chinese accent anxiety.”

“Everyone has an accent,” she replied. “There’s no difference between a Chinese accent and a New York or London accent. Having an accent is nothing to worry about. If everyone spoke with the same accent, that would be something to worry about. It is the differences in accents that make language beautiful.”

This comment did not just capture the essence of language and culture but also became a turning point that helped me reconcile with the anxiety I’d carried since FP.

Looking for My Position

Moving from a Chinese public school to UWC Changshu was a huge contrast. The difference between the two systems is not only about language and curriculum: my previous school encouraged students to be reserved and composed, while UWC Changshu encouraged confident self-expression.

Being “reserved” suddenly felt like a habit I had to unlearn. In middle school, my teachers expected respect and understanding of their educational intentions from students. At UWC Changshu, however, teachers expected a reciprocal relationship and open conversations.

▲My House Meraki,

our group photo on UWC Day

Thrown into this unfamiliar environment, I relearnt and readjusted to nearly every aspect of life. Anxiety arose. The difficulties communicating in English, the Chinese accent I tried to hide but could not, and all the trivial frustrations catalyzed a subtle sense of inferiority.

This feeling grew stronger when I noticed how classmates from international education backgrounds seemed at ease.I could not stop myself from thinking, “Would life be easier if I were like them? Would it be better if I started to be like them?”

What made it harder was that I must hide my struggles. I often felt lost: Who am I supposed to become? Who was I, originally?

It was later that I realized I rediscovered myself at UWC Changshu. Here, I did not need to rush to become someone else. I could simply take the time to understand who I already was.

A Safety Net Woven by People

Many teachers at UWC Changshu kept appearing in my life, offering help, often without realizing it themselves. For them, their kindness and care might have been ordinary, part of their role as teachers. Buttheir support influenced me profoundly. Their acceptance eased my anxiety about “becoming someone else.” They encouraged me to let go of hesitations and simply move forward, to try, and to act.

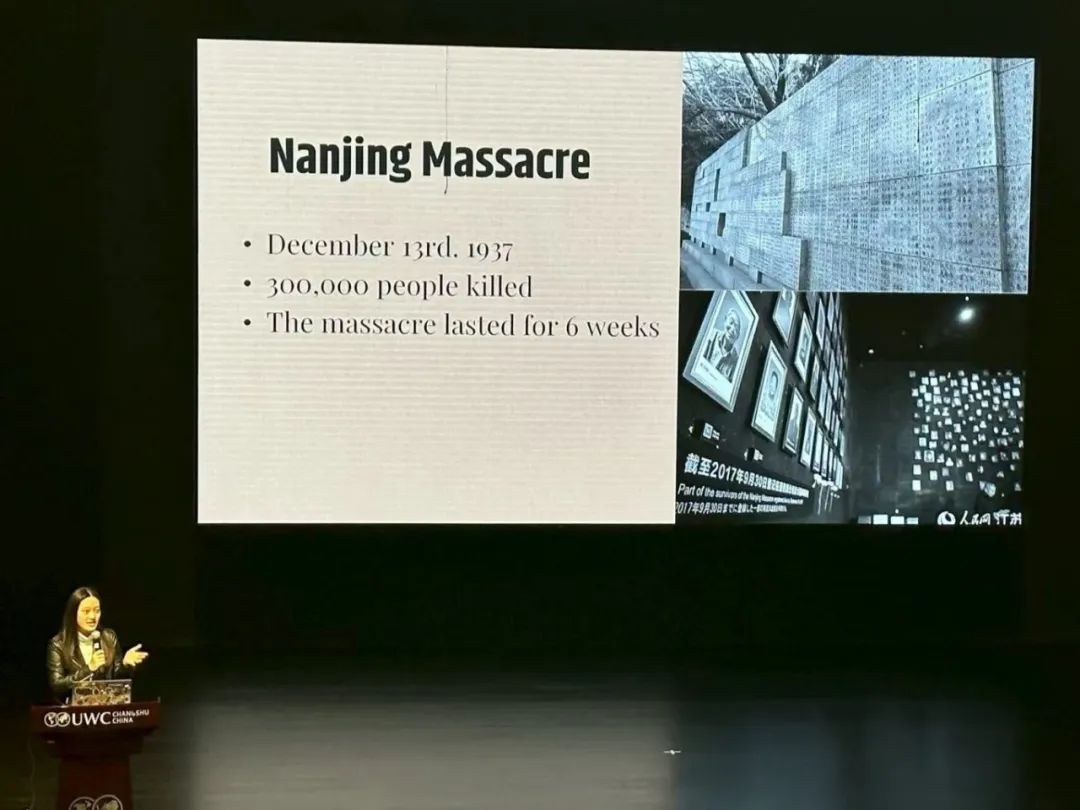

When I organized commemorative activities for the victims of the Nanjing Massacre, my teachers Lusine and Adela gave me the courage to carry on. As a person from Nanjing, I find special meaning in December 13th—the National Memorial Day for the Victims of the Nanjing Massacre. Since FP, I had organized annual memorial activities. In my first year, I created a small historical exhibition, and in the second year, I wanted to reach a larger audience.

Discussing this history in such a diverse community was not easy: it could stir conflicting perspectives or trigger traumatic memories. The topic carried complex emotions.

Unsure about what to do, I thought of my Peace and Sustainability teacher, Lusine, from Armenia. She had once given a lecture on the Armenian Genocide. I reached out for her advice. She responded with full emotional support and connected me with Adela, our psychology teacher from Bosnia, who had similar experience. They helped me reflect on both the value and potential risks of addressing such topics in UWC Changshu’s international community.

Adela shared articles and her own experiences on how to build safe dialogue around sensitive issues. For them, it might have been ordinary instruction as part of their duties as teachers. But to me, fearing all possible outcomes, their words affirmed that my opinions mattered.

I knew any opinion could be controversial and that disagreements were inevitable. I was not sure if I was ready to face them. But their support reassured me: even if my ideas might lead to controversy, my teachers would understand my intentions and be proud of my actions. That sense of having a “safety net” meant a lot.

▲My presentation at the Global Issues Forum

With their support, I chose “post-war reconstruction and reflections on peace” as my topic for the Global Issues Forum (GIF). As expected, there were questions and disagreements, but many people told me they had known little about the Nanjing Massacre, and the forum gave them much to think about. I was grateful to the teachers. They supported me to take the first step and speak up and to embrace different perspectives just as they do.

Support did not only come from teachers—it was formed by the UWC community as a whole. At the Global Issues Forum, speakers, hosts, organizers and listeners worked together to build a supportive and safe space for open dialogue. I was moved by how our community created environments where difficult topics could be discussed, and where everyone felt safe to seek empathy.

▲My friend made Malaysian food for us

Whether discussing global conflicts, wars, or gender issues, participants listened with care and tried to understand others’ perspectives. The trust built among community members existed in discussions, forums, and all aspects of our daily lives.

During DP1 Project Week, we traveled to rural areas in Henan to give workshops at a local middle school. Some of our workshops were on dance. After class, our group member Mariana from Mexico suggested we explore the streets and join the local aunties for square dancing. We learned their dance. Before long, we were teaching them Latin dance. At a busy intersection, we used the aunties’ speaker and took turns performing dances from different cultures.

▲We organized a dance workshop at the middle school in Henan Province

That was the first time I felt the joy of dancing. It transcended language and skill, becoming the purest form of emotional expression. It was about the positive emotional feedback we felt from each other’s eyes, how we were influenced by our surroundings, and how we used bodily language to share that joy.

It was a mutual transmission of excitement built on our trusting and relaxed relationships. In the music, no one cared if our steps were perfect or how the audience judged us—we were connected through movement, releasing our emotions and letting that joy ripple outward. This experience would have been impossible without my peers.

▲Fuego Latino's performance at the One World Concert

This experience later led me to join Fuego Latino, the Latin dance Zhi Xing, in DP2. At first, I felt awkward about some movements and feared the attention. But the warm atmosphere of the Zhi Xing helped me gradually let go.

I stopped seeking recognition from others’ eyes and stopped tying my confidence to how I was judged. I gradually discovered the joy of dance as pure self-expression, focusing only on what I felt.

This change extended beyond the stage and influenced my perception of myself. The passion I found in Fuego Latino motivated me to try different arts and dances from various cultures and seek opportunities to express myself.

During the application season, when I worked under great pressure, dance became my most precious emotional outlet. The memories of all performances remind me of the people who led me out of my comfort zone. Their confidence showed me that true self-expression doesn’t require perfection—only sincerity.

Discovering Myself in Aimless Drifting

I was able to explore deeper at UWC Changshu with this sense of safety as a foundation. I let my random thoughts and spontaneous decisions guide me. In the process, I could gradually see my personality more clearly and think more deeply.

In DP2, I continued discussing the Nanjing Massacre at Global Cafe during Asian Week. Again, I was supported by my community members. Surprisingly, I felt my fear and anxiety becoming lighter. I designed questions and prompts to elicit different perspectives and looked forward to diverse voices.

Teachers and students from Nanjing, Armenia, Israel, Australia, Japan, and Malaysia sat around the table. We started with the massacres in Nanjing and Armenia and extended to protests by Aboriginal people in Australia and wars in Israel and Palestine. We discussed how the representation of trauma in media narratives slowly influences understanding within communities.

We explored how dehumanization, simplification, and labeling erase humanity and make violence easier to accept. Some of us had experienced conflicts, while others were far from wars, but we all grew up reflecting on our histories. We wrestled with the same questions: as young people, how should we face the traumas of our own nations and those of others? How should we remember traumas?

We didn’t have the exact same answer, but we were surprised to discover the consistency running through each other’s answers: on different sides of conflicts, we could look each other in the eye and bridge our differences to pursue the emotions that connect our common humanity.

Over the past three years, discussions on this topic have made me increasingly appreciate its value in this special community. Members kept adding value to the topic with their own understanding and experiences, giving the discussion of history a present-time weight and warmth.

Memorial activities for the Nanjing Massacre were something I was determined to continue, each time gaining unexpected feedback. Some of my UWC experiences, however, began almost by accident yet still grew into something meaningful.

▲Our martial arts performance at CCE

Most of our members had no prior experience in martial arts or even in any sport. Every movement and routine required countless hours of practice, patience, and teamwork. We kept making mistakes in rehearsals. We doubled our efforts to train, but new mistakes always occurred in the next rehearsal.

Take“Zhige,” the martial arts Zhi Xing. I had never been part of any athletic team activities. The idea of cheering, celebrating one goal, or crying as a group for victory was somehow unimaginable to me. But by chance in FP, I joined Zhige, started training, and later, in DP1, became a core member, eventually coaching others and helping choreograph for the Chinese Cultural Evening (CCE).

Most of our members had no prior experience in martial arts or even in any sport. Every movement and routine required countless hours of practice, patience, and teamwork. We kept making mistakes in rehearsals. We doubled our efforts to train, but new mistakes always occurred in the next rehearsal.

However, amidst all the mental breakdowns, we forged a special friendship. On the day of CCE, I stood backstage, watching our members flawlessly perform the movements that had repeatedly gone wrong before. I saw their strength and performance peak, their passion and excitement, and the sparks flying from clashing swords.

Members backstage cheered, screamed, and hugged. As an organizer, seeing my team explode with such energy brought me a kind of joy I had never experienced before—raw and electrifying.

Before becoming Zhige’s co-leader, I had doubted my ability to lead. I was gentle by nature, uncomfortable giving orders or making people do things. Zhige taught me that leadership doesn’t have to rely on toughness. I learned how enthusiasm, fun, and creativity were enough to motivate people to persist through grueling training. Zhige reshaped my understanding of my capabilities, my personality, and my way of working with others.

Finding My Cultural Identity in the Global Island

At UWC Changshu, the question “Who am I?” was asked again and again. Gradually, I found more answers—not just about how I think or what kind of person I am, but also about what shapes me. Culture became central to this question.

As someone deeply connected to Chinese culture, I once worried that an international environment might dilute that identity. But instead, the opposite happened: surrounded by diverse cultures, I came to see my own roots more clearly.

The more diverse our environment was, the more tightly we held onto the cultures that defined us. That’s why at UWC Changshu, students eagerly shared their traditions during Cultural Weeks and UWC Day.

▲Playing erhu at CCE

Among these, the Chinese Cultural Evening (CCE) was especially meaningful to me. On that stage, through erhu, martial arts, and other traditional arts, I could sincerely express my understanding and love of Chinese culture.

Over the years, I grew from a performer to a planner and host. Despite increasing academic pressure, I invested more time and emotion in CCE, realizing that cultural expression is not about flawless art but about sharing what we love.

▲I (first on the left) served as the host at the 2025 CCE

In UWC’s English-dominated environment, I had worried I would lose my Chinese, my native tongue. But the Chinese classes here eased my fears. The teaching was not only as rigorous as in traditional schools but also more expansive—it made Chinese a language to be felt and lived.

I remember FP Chinese class debates on Cao Yu’s Thunderstorm. With our teacher Lei’s guidance, we dissected the complex psychology of characters like Fanyi and Zhou Puyuan, uncovering roots of conflict linked to broader issues of class and gender inequality. Our debates became so heated that we nearly started arguing. Yet it was this intensity that revealed literature’s value to us: its conflicts still mirrored the real world.

In DP, our teacher Jacky often brought us outdoors to read poetry by Lo Fu by the lake. In nature, we imagined the crying cicadas and camellias stained with blood in the poems, encouraging us to feel the poetry in the most personal ways.

When we studied Hibiscus Town, our group presentation on Wang Qiusheng sparked broader discussions: Was he shaped by his era, his environment, or his character? Naturally, we extended the conversation to real-life parallels, reflecting on Gu Hua’s intent and the reader’s lens. Literature, once a rigid academic exercise, became a tool for observing life and the world around us.

UWC’s Chinese curriculum gave me the chance to rediscover my mother tongue—not just as a subject or a grade, but as a way of thinking and feeling.

Make Every Place You Go a Little Like UWC

I also remember a tour to the Changshu Museum. My friend and I led international students new to the city to understand its culture. During the trip, we talked about academic pressures. I asked, “Many Chinese students have the stereotype that international students don’t care much about grades. What do you think?”

▲Our tour to Changshu Museum

She replied, “That’s both true and not. Of course we care about grades. But there are IB schools everywhere. If all I wanted was a high score, I could have stayed at home. Traveling half the world to come here—I clearly came for something more.”

Her words stayed with me. They reminded me of UWC’s meaning beyond academics and pushed me to embrace what only this place could offer.

Looking back to my UWC interview, I had memorized the values but questioned them. Could a high school really pride itself on idealism? Could a group of teenagers truly pursue “peace and sustainability” and all those grand visions? They seemed vague.

Now, at graduation, I still haven’t accomplished those “grand” goals. But in small, quiet ways—inwardly through self-discovery, outwardly through influencing those around me—my journey has echoed those ideals. More than knowledge or skills, UWC has deepened my understanding of myself, given me the courage to stand by my values, and the confidence to share my true self with others.

I realize now that in FP, I had been chasing a false premise: trying to “become the right kind of UWC student.” But there is no such image. UWC is built on embracing individuality. No one should have to change themselves to belong here.

▲Me and my advisors

At graduation, I told my advisor, “I feared these three years would be the most exciting moments of my life. But I also believed they might just be the beginning.”

My advisor replied, “You can try to make every place you go a little like UWC.” It was pure UWC idealism—optimistic, perhaps unrealistic. And yet I hope for it.

-End-

Article by Xiaoshu Zhu, Class of 2025 UWC Changshu China, Class of 2029 University of Chicago. Part of the photos credited to Jayda (Class of 2025) and Eileen (Class of 2026).