The COVID-19 Crisis and Reflections on Education

Issue date:2020-04-16Practicing social distancing at home, I cannot help but be amazed at the pace of events in the world over the past 3 months. When I left Changshu for Chinese New Year, news regarding an outbreak of COVID-19 started to appear. Now, the whole world has come to a standstill; while death tolls continue to rise, desperate action around the world strives to put a stop to this global health pandemic.

In 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, historian Yuval Harari draws a hyper-realistic picture of the modern age: a world where we are incessantly bombarded with an enormous amount of information; where exponential change and uncertainty are the only constants in life. With the onslaught of COVID-19, this reality has been exemplified.

Adaptability in rapid pace of change

Working in a sector notorious for its rigidity and slow pace of change, I think that what is happening in the world is a wake up call to all educators regarding the purpose of what we do and the quality of the work we are actually doing.

Are we (educators, parents, university admissions officers, policy makers) finally brave enough to admit that scoring well in a standardized test has no implication as to how well a student might do out in the ‘real’ world? We must critically examine how education is cultivating the adaptability and mental resilience of our students. The world after COVID-19 will not slow down. Technology and automation will force students to change occupations, pick up new skills and adapt to the modern world over and over again, throughout their long lives ahead. Living through such rapid change can be debilitating; students will have to learn to be mentally strong as the pace of change accelerates.

Adaptability, the ability to acquire new skills along the way, is required to adjust to changing conditions in different contexts. Learning how to learn will take centre-stage. Education must help students develop metacognitive skills to help them grasp not only what they are learning, but how they are learning. Metacognition, simply put, is the know ledge of one’s own thinking and learning processes. By ‘knowing’ (beyond simply practicing) one’s range of strategies for learning, thinking and problem solving, students can transfer and adapt their learning to new contexts. Knowing one’s learning strategies also encourages students to select, plan and use them appropriately when handling different tasks.

How do students learn how to learn? The good news is, metacognitive skills can be taught. What we need is a focus beyond ‘what’ students are learning but also how they are learning. Knowing the ‘how’ will serve students well long after they leave the classroom, increasing their adaptability to tackle upcoming challenges and situations.

We can all help. Some questions we (parents, teachers, friends) may ask students to cultivate their metacognition during distance learning:

· What were some of your most powerful learning moments and what made them so?

· What did you realize about yourself as a learner?

· How did you learning this week fit into my broader goals for developing myself?

· How did you manage your time, and did you have a healthy routine?

· What most got in the way of your learning progress, if anything?

· What is the biggest progress made? How do you plan to address challenges and difficulties if there were any?

UWC Community and mental resilience

Adaptability alone is not enough in face of a rapidly evolving crisis; adaptability must be accompanied by a high level of mental resilience when the world is seemingly out of anybody’s control.

Research on resilience and grit highlights the importance of education in helping students instil positive mindsets. At school, a supportive, close-knit community helps students build resilience when they feel a sense of belonging to a community, where members provide each other support and encouragement. Students come to believe that, with effort, they can succeed in work valued by the whole community. There in lies one of the greatest challenges we face in this period of distance learning: to uphold a sense of belonging to a unique, shared community. At UWC Changshu, when all of us are physically on campus, students learn, play, eat and live on an island which we call ‘home’. Our deliberate diversity across cultural, ethnic, racial, socioeconomic lines, in pursuit of the UWC mission, fosters empathy and international understanding in everyday community living. Spread all over the world as we are now, it becomes more difficult to feel the connecting threads of this supportive culture.

The author (center) with her advisory group at the beginning of the school year.

Yet our faculty and students bring me hope. Students in my DP2 Economics class have impressed me with their persistent motivation to learn, despite many challenging personal circumstances from poor internet connection, familial duties, to financial difficulties. Digital connection will never be the same as human touch; yet I see students making the best of the means at their disposal. They exchange stories on TEAMS chat, share notes with those who have left notebooks behind at school, send ‘stickers’ of support and ‘likes’, pour out their good wishes in virtual ‘open mic’. I am confident that the community bond, while stretched by distance, nevertheless remains intact. Faculty members too have embraced the use of familiar and unfamiliar technologies and ways of working without reservation.

Systems thinking to tackle complex global challenges

Not only is the speed of change in our world daunting, COVID-19 has shed light on the complexity of the contemporary issues we face. The UWC mission of promoting peace and a sustainable future looks more challenging than ever. The outbreak of this global health crisis encompasses dimensions far beyond health. Take for example, the intricate relationship between our health, climate and other organisms which cohabit the planet. Many of the root causes of climate change also increase the risk of pandemics, demanding carefully coordinated public policy response. Analysis of the causes and consequences, and development of appropriate responses require systems thinking: to examine the whole picture of how different system elements interact with each other in an integrated, interdisciplinary approach. Only then can we change the patterns of harmful embedded systems.

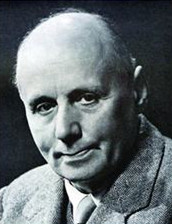

Different elements in our curriculum cultivate habits of systems thinking. In Economics, the concept of externality highlights the impact on third parties that are not recognized by the free market, leading to socially sub-optimal market outcomes. When analysing industrial activities through the lens of externality, students must examine short term, long term and unintended consequences. In Foundation Program Circular Economy, students utilize systems maps to identify stakeholders and feedback loops in systems at school (e.g. the mailroom, or canteen), in search for ‘circular economy opportunities’ where they could redesign linear systems to reduce waste. As researchers at the Abdul Latif Jameel World Education Lab at MIT point out, systems thinking engages teachers and students in “reflecting on their ways of seeing and becoming more explicit in constructing and testing their own models of reality.” More than ever, it is critical for our students to pay attention to reality in its fullest, complex form, to recognize the assumptions of our models, the dynamic nature of systems and not-so-obvious elements which intersect in our economy, society and planet.

Sample systems map by a group of Foundation Program students on the food waste treatment system at school.

Design for change

People often ask “what makes a UWC student different?” My answer has always been: “the inclination to take action.” UWC students care. They empathize with others. They are observant and are sensitive to the problems in the world. And since they care deeply, unlike most people, they do not stop with caring: they possess the disposition to take action to make the world a better place.

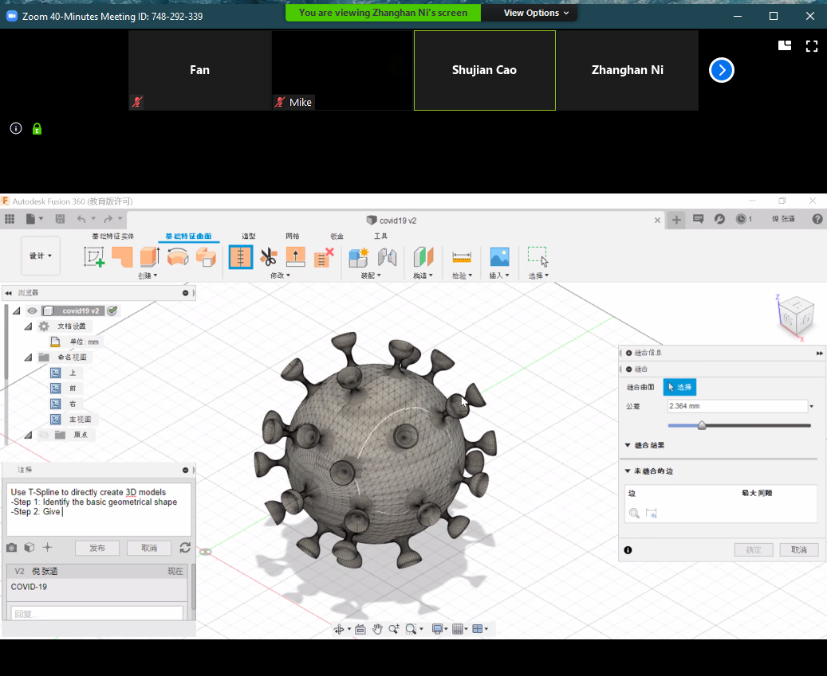

Our FRC robotics teams serves as a wonderful example. The team has taken the initiative to launch a program during three consecutive weekends for middle school students to design robots that would inspire ideas to help improve public hygiene condition given the global health epidemic backdrop. The students designed the curriculum, with a goal not only to teach younger students the use of Computer 3D software, but more importantly, to teach them the design thinking cycle, empowered by Computer Aided Design (CAD) to ‘design for change’.

Screen capture from UWC Changshu FRC Robotics Team online CAD class.

Are all UWC students like this when they enter school? No. Yet most have the ‘seed’ that will grow into the impetus to act. UWC education cultivates future change makers by strengthening their capacity to analyse complex issues, and empowering them with the ability to adapt and learn new skills. With a supportive, compassionate community, we hope to instil in them the positive, strong mindset needed to engage in the long, iterative journey of change making.

Our students make me look forward to the world after COVID-19.

References:

1. Bransford, John, et al., editors. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Expanded ed, National Academy Press, 2000.

2. Harvard C-CHANGE, “Coronavirus, Climate Change, and the Environment”, hsph.harvard.edu, Web, 20 Mar. 2020.7 April. 2020.

3. Boell, Mette, et al. Introduction to Compassionate Systems Framework in Schools. Abdul Latif Jameel World Education Lab, Massachusetts Institute of Technology The Center for Systems Awareness, 2019.

4. Paul Tough, “How Kids Learn Resilience”, The Atlantic, Web, June2016,7 April. 2020.